- Home

- Jimmie Walker

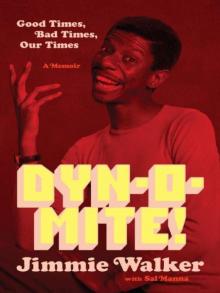

Dynomite!: Good Times, Bad Times, Our Times--A Memoir Page 2

Dynomite!: Good Times, Bad Times, Our Times--A Memoir Read online

Page 2

I didn’t want to hear any of that. I was from New York! The Joneses were just people—nothing special, even for white people. But I could never say that to Aunt Inez. She has been dead these many years, and even now saying something against her, I am afraid she still might come after me!

I met a few white people back in New York during my first job—shining shoes outside nearby Yankee Stadium in the Bronx when I was ten years old. A little later I delivered newspapers, the New York Post, mainly to Italian families, on a route just outside the projects. But I never really knew white people until I became a vendor at the stadiums when I was fourteen years old, beginning with Yankee Stadium but also at Shea, the Polo Grounds, Madison Square Garden, and so on. Most black people, including myself, were not especially interested in them or their culture. What surprised me was that they, especially the Jewish kids I worked with, were interested in mine. They wanted to know about our music, our lives, everything.

They were the first people I ever met who had drive, who wanted to do something with their lives. They weren’t working selling peanuts and soft drinks to buy a new $12 pair of Flagg Bros. shoes. They were working to earn money to go to college so they could become doctors or lawyers or open a business. To them, if you didn’t go to college—even a lousy college—it was nothing short of shameful. Growing up in the projects, I could not conceive of such a plan—few of us could. Education? That was for someone else. In the projects you didn’t think about the future. There was no future; there was just today.

They were white and Jewish, guys like Gary Cohen and Alan Marcus, but we became friends. They had cars and would come into my neighborhood to pick me up to go to work. They introduced me to the Stage Deli and invited me to the Huntington Townhouse, an iconic banquet hall on the Jericho Turnpike that hosted bar mitzvahs and weddings. I would put on the inscribed yarmulke and—this is probably not a shock—still stand out in the crowd. These were progressive people, and to some extent I was a trophy: “Hey, look at us. We got a black person here! We’re not racist!”

I used to have a bit in my act about going to the Huntington Townhouse on Saturdays.

Gary Cohen would get dressed up in a nice powder-blue suit, put on his yarmulke, and I’d go with him. With twenty bar mitzvahs going on, he’d just walk around and pop into a room every now and then. Inevitably, some woman who hadn’t seen her designated bar mitzvah boy since he was a child and could not possibly identify him would say to her husband, “Harry, that must be him. Give him the envelope and let’s get the hell out of here.” We’d take in a couple grand a weekend!

That was only a joke, but I bet that scam would work today.

The extent of my criminal life involved the Great Candy Caper. About a mile away from the projects was a candy factory. Talk about temptation. I loved Chunkys. A Chunky was a candy made of milk chocolate and filled with raisins and peanuts. They were originally made in New York and had been around since the 1930s. They were beautiful and delicious, and when I was a kid, one Chunky cost only five cents. This factory had lots of other candies, but the Chunky was my pot of gold.

One night several of us kids broke in. It was not difficult. This was the late ’50s—a very different time in our country. There were no razor-wire barriers or security dogs or burglar alarms. We crawled in through an open window. We weren’t exactly criminal geniuses. We didn’t realize until we were inside that we hadn’t brought anything with us, like shopping bags, to help carry out the loot. So we took only what we could put in our pockets or carry in our arms. Still, a few dozen boxes of Chunkys, and Clark and Hershey bars were a good haul, and we ran happily home.

By the time I reached the lobby of our building the word was out that the police were looking for the guys involved in the “candy heist.” How they found out so fast, I didn’t know—maybe the police tracked us down following the candy we dropped along the way, a sort of Hansel and Ghetto. When I got into our apartment, I stashed the Chunky bars under my bed and prayed the police would somehow skip my place in their search for the culprits. When you’re a kid, you don’t know what trouble is until you get into it.

About ten o’clock that night, the knock came. It was not a neighbor’s knock or a salesman’s knock; it was an “official” knock on the door. My mother answered.

Two policemen stood there. “Mrs. Walker, we have it on good authority that your son stole some candy from the factory nearby. We’re here to get the stolen property back or make sure there’s restitution.”

Cowering in my room, I heard them, but still hoped I would not have to come out to face my mother.

She came into my room instead. “Did you steal that candy?”

At first I went with, “What? Candy? Huh?” It did not work. She walked me into the living room, where the policemen stood.

“Look, Mrs. Walker, we will take him downtown to juvie if he doesn’t fess up. We know he was one of the kids.”

I saw the guns in their holsters and the billy clubs in their belts.

“Um, but it wasn’t my idea,” I said. “It was John Westbrook.” He had stolen my baseball glove, so I figured he was fair game.

“Do you have any of the candy? We’ll look if you don’t show us.”

I pulled out the boxes from underneath my bed.

“Alright. We might come back again for more information.”

As they took away the Chunkys, I was quivering.

My mom said, “Why did you do something like that? You know that was wrong. No, I can’t buy you a dozen Chunky bars, but I can get you two. How many do you want? Because you’re not going to get a dozen. Now go back into your room, and I don’t want to hear anything more from you.”

The next day, when all of us kids got together, we were tough guys once again.

“Yeah, the police came, but I told them I didn’t know nothing! I don’t know if anybody squealed, but it wasn’t me!” That’s what each of us said. Of course, every kid had ratted out at least one other kid. Nobody was going to admit how really frightened we were. Maybe I just learned life’s lessons really fast, because the Great Candy Caper scared me into never stealing anything again.

I hung out with a group of guys in the projects, but we never called ourselves a gang. My buddies had nicknames like PoPo (the funniest of the group), Head (very quiet, but we listened when he spoke), and Gooie (the best looking of us). There was also Irving Lipscomb, who was black even with a name like that. I know we were not really a gang because there has never been a gang with a member named Irving. In any case, Irving was two sandwiches short of a picnic.

We were barely teenagers, but we thought we were pretty tough, at least when we were together. The Melrose, Patterson, St. Mary’s, and Highbridge projects as well as neighborhoods such as St. Anne’s—each had their own turf. At Melrose, John King was our leader. He was the fastest and the strongest. Once, we were on St. Anne’s turf, and they came after us. We ran and we ran and we ran. They targeted King and somehow caught him. They beat the crap out of him. Today, an inner-city gang would probably just shoot the other gang member dead without a second thought. But for us back then, they subjected King to the ultimate insult—they made him say, “Mommy.” Only then did they let him go.

When we next saw John King, who we thought could kick anybody’s ass, he was a beaten lad. Seeing that happen to someone was frightening and sad.

Another time we went to the Highbridge projects at night for a dance at somebody’s apartment. When the Highbridge guys heard we were there—and hating that we might be dating Highbridge girls, which we were—they busted in. One of them had a machete.

He yelled, “I am going to kill anyone from Melrose or anyone I don’t recognize!”

I jumped head first out the two-story window and into the bushes below. My buddies followed. The Highbridge guy then swung his machete out the window hoping to hit one of us. I figured he was then going to rush downstairs and intercept us as we crossed in front of the main building. Scared and scratched up f

rom the jump, we hauled ass. Through back alleys, with dogs chasing us, we never stopping running for the entire eight miles home.

We had trouble at Patterson too. When you got off the subway one stop before ours for Melrose, you had to walk through the Patterson projects. If the Patterson guys saw us, they would chase us back to the border with Melrose. Conversely, when they came to our projects, we did the same to them. The lines were pretty well drawn. The problem was that at junior high school you met girls from Patterson and elsewhere. If you wanted to go out with one, you would have to venture into enemy territory to pick her up because her parents wouldn’t allow her to come to your neighborhood alone.

Then there were the Italian guys, who had a real advantage because they had cars. We would sit on the stoops in front of our buildings and see them drive into our neighborhood. Someone would yell out, “Dagos on the way!” We would duck behind a bench or run behind a building because they would shoot at us! I guess that was their sport—hunting niggers in the projects. We were the targets of their drive-bys. Today, a gang would blow you away with firepower. Back then they were playing with BB guns or .22s. Nobody was likely to get killed.

But when my friend Ronald Wiley scooted behind a building, a bullet ricocheted off the bricks near him. A piece of the broken brick hit him in one of his eyes, ripping it out of the socket. The eyeball hung by the nerve as he held it in his hand. There was blood everywhere. We took him to the hospital. They took the eye out and put a patch on. Eventually they gave him a glass eye.

I admit it—I was never a fighter. I only got into one fight. I didn’t want to be involved, and when I was, I wanted it over as fast as possible. The only detail I remember is that the guy sprained his back and screamed. That was all. That was the end of my career in street violence.

Despite the turmoil at home I managed to avoid getting into drinking or drugs. In fact, I have never done any drugs and I have drunk alcohol only once in my life. I know what you’re thinking: “Oh yeah! You are telling me that someone in show business, a comic on the road for hundreds of days a year, doesn’t drink, do drugs, or smoke? What is he, some religious freak, someone on a morality crusade?” Neither, my brothers and sisters. I did not follow the Ten Commandments as written in the Bible. I followed the Ten Commandments as seen in the reality show. I saw what not to do by watching the people around me. I was influenced by good examples of bad examples.

For example, there were my mom’s younger brothers, Cornelius and Herbert. They would drive down from Connecticut to visit on a Thursday and they would stay drunk through Sunday. Cornelius had a reason to drink: When he was a child in Alabama, the Klan threw a torch under their house. Turned out that was where the kids were hiding. His shirt caught fire and burned one of his arms to the bone. It was a shriveled, hideous-looking thing that was puffy and sometimes oozed a yellowish pus.

Before he would visit, a well-meaning person would tell everyone, “Do not say anything about the arm. You understand me? Do not say anything about the arm.” Cornelius would enter and, of course, someone would be so shocked they’d blurt out, “Oh my God, what happened to your arm?”

He was taunted and laughed at and made miserable all of his life. He drank to numb the pain, both physical and emotional. Herbert kept up with his brother’s drinking too. Both of them were short men and had a Napoleon complex. They would challenge people to fight at the drop of a hat. If you looked at Cornelius’s arm, Herbert would get in your face and say, “What the hell are you lookin’ at, man?”

“Nothin’.”

“Bullshit!” And the fight would be on. With just one arm, Cornelius wasn’t much help. Most of the time they would get their heads kicked in.

When they arrived on Thursday, I liked Herbert and Cornelius. By Saturday night, with all of the fighting and drinking, seeing them laying in their own vomit, I wished they had never come. I saw people such as them change, get totally out of control when they were drunk or high, and that never seemed like fun to me.

My mother would ask them to take it easy with their drinking. But they could not.

“Mom, they’re drunk!” I complained.

“They’re your uncles. Shut up.”

My mother loved her brothers, no matter what. She loved her kids too. She was always good about talking to us about drinking and smoking.

For her brothers and herself, she kept a stash of Canadian Club whiskey and cartons of Chesterfield cigarettes. “If you want to drink, you want to smoke,” she told us, “it’s right there. Do whatever you want. Go right ahead. I’ll leave it right out for you. But here’s what’s going to happen when you drink. You’ll feel good for awhile, but then you are going to get sick to your stomach and throw up. You’re going to have headaches, get splotches on your face, and start to look really old. Your eyeballs will turn red. You’re going to stumble around and fall down.”

Nothing good about any of that, I thought to myself.

“If you smoke,” she went on, “this is what’s going to happen to you. You’re going to have bad breath. Your teeth are going to get yellow. And you’re going to cough all the time. If you want that, go ahead.”

No, really, thanks anyway.

The only time I ever drank was when I was fifteen. We were at the YMCA. Someone brought Ripple wine and I kept drinking from the bottle. It tasted terrible. Then, just as my mother said, I got sick. My friends pushed me into the bathroom. I put my head into the bowl and vomited. Someone then flushed the toilet with their foot. I took my head out and then put it back in—and passed out. I became so ill that my friends had to carry me home. I stayed in bed for two days. My mother never asked why I was sick. She didn’t have to.

I never drank again—even when I went to bar mitzvahs and they would always have Manischevitz wine there.

“It’s just wine, not hard liquor,” they would say.

“That’s okay. Is there any Dr. Brown’s soda?”

My mother was the same when it came to curfews. The rule for many kids in my neighborhood was that when the streetlights went on, that was the signal to come home. My mother told us, “I will be at work. I can’t watch you. Come home when you come home. Try not to get into trouble.”

I did not get into much trouble at school. After all, I was hardly there. When I was, I sat at my desk, looked out the window, made paper airplanes, and shot spitballs. I don’t blame the teachers for their lack of interest in guiding me. Almost all of them were white, and most of them did not want to be there either. But if you were a teacher, you could avoid the draft. So here they were in the ghetto wondering, “How the hell am I going to get my car out of here in one piece after class?”

I took a twisted pride in the fact that I handed in the same essay in English class from the second grade to the ninth grade. It was about Jim Gilliam, a black infielder with the Brooklyn and Los Angeles Dodgers. It never got any better either—always earning a B or C.

One day I was in front of Yankee Stadium shining shoes, and there was my hero! He was dressed in a brown tweed suit, driving a brown Caddy, and on his arm was a beautiful brown-skinned woman. I thought he was the coolest dude I had ever seen. He handed me a buck to shine his shoes and I told him all about himself, quoting my essay. When he gave me his autograph, it was one of the biggest thrills of my life.

I found out why the Caucasians are better at school than we are. Because y’all are better cheaters! The white kids had the answers to the tests all written up and down their arms. I tried that one time and almost went blind!

The only class that appealed to me when I was at Broncksland Junior High, JHS 38, was music. I fell in love with the saxophone when I was nine years old and I begged my mother to buy me an instrument, the only thing I ever wanted her to buy me other than baseball gloves. I don’t know how she did it, but she bought me a Selmer sax, the best on the market, at a pawn shop. I was in heaven. I took that Selmer Mark VI alto sax to school and they put me in the band. For a while music was the only reason I went to schoo

l every day. I thought that when I grew up, somehow my life would involve playing the sax, like Paul Desmond in Dave Brubeck’s band. But I never got the hang of actually reading music. I probably sounded terrible, but I didn’t care—I loved to play.

The girls loved it too, and that was a very good thing. After one talent show in the assembly hall, the audience applauded my solo. I went into the hallway, and a crowd of girls gathered around me.

“My God, you are incredible!” they said.

No one beyond my mother had ever said I was incredible doing anything. I’m sure I was awful, but it didn’t matter. The girls thought I was incredible. I was one cool thirteen-year-old boy, all dressed up in a white shirt and black pants. I looked like a clarinet playing the sax.

“What’s your name?” they asked.

I said, “Sax.” And that’s what I began calling myself.

I was in every band in the school and lots of groups outside school—jazz, classical, pop. I wasn’t very good, but I was enthusiastic. One teacher gave me some valuable advice I still believe to this day: “If you’re going to be wrong, be wrong and be strong. Play it, don’t fake it. Play it!”

I so wanted to get better, but we couldn’t afford private lessons. In fact, there were times I didn’t even have a sax to play. We would have to pawn it for extra money. My sister would say, “He can’t play that thing. He’s never going to do anything with that. He’s never going to be anything. I’m going to go to college.” She would want the money for French tutoring or classes to help pass the SAT. My mother would agree and hock my sax at the local pawn shop for $50 or $100. When it would get close to the 120-day limit at the shop, we would get that note saying if we did not pay the loan with interest, the sax would be put up for sale. I’d hustle, working more stadiums to make sure I did not lose the sax forever. That sax was in and out of the same pawn shop time and time again. Every time I had to give it up was painful.

The All-City band was selected from the best junior and senior high school players after an audition in front of Mercer Ellington, Duke’s son. I was so determined to try to get in that for the only time in my life I asked my father to drive me somewhere. Because he thought Duke might show up, whom he adored and had met at Penn Station, he agreed to drive me to the audition downtown in the ’56 Buick he had never allowed us even to sit in.

Dynomite!: Good Times, Bad Times, Our Times--A Memoir

Dynomite!: Good Times, Bad Times, Our Times--A Memoir