- Home

- Jimmie Walker

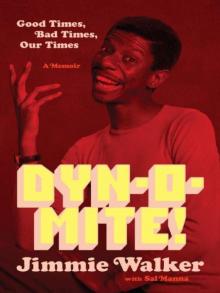

Dynomite!: Good Times, Bad Times, Our Times--A Memoir Page 20

Dynomite!: Good Times, Bad Times, Our Times--A Memoir Read online

Page 20

In LA everybody is a star or thinks they will be one or is sure they should have been one. That may be Angelina Jolie eating at Denny’s, but her waitress knows she could have been just as big a star if she had had the same breaks. The valet parking my car could care less about Jimmie Walker. He is positive that he’s funnier than I am.

In Vegas or anywhere outside of LA people treat you as something special because they recognize you. There is a lot of “Oh wow, it’s you!” Okay, but I already know it’s me.

Moving to Vegas put some distance between me and Hollywood and also gave me an opportunity to do other things in life. Like playing music. I took out the same sax I had when I was a kid, which I had kept all through the years, and started practicing.

I was still terrible.

Nevertheless, I enrolled in the Music Department at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas (UNLV) as an auditing student. I was a thirty-something on my first day at college.

I even asked if I could be a member of the pep band. Amazingly, they said yes. The band was filled with eighteen- to twenty-two-year-olds who had already been playing ten years or more. They were really good—better than the All-City band in New York that was out of my league when I was a teenager. Just among the other sax players were Cleto Escobedo III, whose Cleto and the Cletones became the band for Jimmy Kimmel Live, and Paul Taylor, who would later have hit jazz albums.

The instructor gave us music sheets and expected me to play like Cleto and Paul. Uh, sorry. Fortunately, the teachers and students in the music department were understanding and willing to give me the private lessons I could not afford as a kid. But I never got much better. I was what they called a “manpower player”: I didn’t have to be good—I just had to make a lot of noise! But playing that sax—my old sax—was so much fun.

We were often on the road four days a week, playing for the crowds at football and basketball games and special events. At the time UNLV was a basketball powerhouse, with future NBA stars like Larry Johnson, Stacey Augmon, and Armon Gilliam. Arenas were filled with upwards of twenty thousand fans. We traveled just like the team—even had our own bus. We checked into hotels at one or two in the morning and practiced in banquet rooms during the day. We went all over the country, from North Carolina to Chicago, Maryland to New York and Houston. It reminded me of my days traveling with the Motortown Revue—and still there was that one person on the bus able to sleep through all of the noise.

I kept my “day job” back in Hollywood and went to work for a producer who was very different from Norman Lear. Aaron Spelling had already produced the hit TV series Starsky and Hutch, Charlie’s Angels, The Love Boat, and Fantasy Island (I had starred in episodes of both of the latter), and he would later be responsible for Beverly Hills, 90210 and Melrose Place. What Lear was to half-hour comedies, Spelling was to one-hour dramas. As soon as Good Times was canceled he cast me as a former car thief trying to stay straight in a police drama series called B.A.D. Cats (B.A.D. as in Burglary Auto Detail).

After all of the heat surrounding Good Times, B.A.D. Cats was a welcome change of pace. Spelling was simply into the game of network television—having hits, making money, and moving his chips around. Unlike Lear, he was not trying to deliver a message. They had very different styles too. Where Lear acted like the local head of the Parent Teacher Association, Spelling acted like the president of the United States.

When he was about to visit the set, a runner informed us, “ETA on Aaron. He’s coming by to talk to you in nine minutes.” Later: “ETA on Aaron. Here in two minutes.” Then two security men showed up. Then E. Duke Vincent, Spelling’s right-hand man, with his Palm Springs tan and gold chains around his neck, walked onto the set. Finally, at exactly his appointed time, came Spelling.

“Hey, I love the show. The network thinks it’s great. Keep doing what you’re doing. Gotta go.” Then he exited with his entourage.

B.A.D. Cats was an easy gig—two hours a day, three days a week. But the series only lasted six episodes on ABC. Today the show is remembered only for being an early role for a young actress named Michelle Pfeiffer, who played a policewoman nicknamed—believe it or not—Sunshine. Michelle was about twenty years old and always so excited. At lunch she would say, “This is great! I’m going to be in all the magazines! I’m going to buy a house in Malibu!” Turned out she did become a star, but not thanks to B.A.D. Cats.

A couple years later Spelling decided to give sitcoms a try and pulled me in for ABC’s At Ease, which was about a couple of conniving guys in the army. We had so much fun on that series. Unfortunately, the show was not funny at all. We were gone after three months.

Bustin’ Loose, however, had a chance. Based on the Richard Pryor film, I starred along with Vonetta McGee in the all-black cast of the syndicated sitcom. I was not keen on doing another “black show” and the pressure that goes with it: Is it relevant? Is it black enough? But I had them hire Allan Manings from Good Times as a producer, whose experience I thought would help. I played Sonny Barnes, a former con artist working through five years of a community service sentence under the supervision of a social worker raising four orphans. I hoped Bustin’ Loose might go on for a few years. But after one season we were off the air.

All along I was also doing game shows, which gave me tremendous exposure and helped promote my club gigs across the country. Shows like Hollywood Squares proved that I could ad-lib. I know they gave funny answers to some of the stars—Paul Lynde, Rose Marie, and maybe one or two more—but not to the others, not to me. Those shows also kept me in touch with friends from my days at the Improv in New York, such as Stiller and Meara, who were frequent guests and brought their kids, Amy and Ben, along. Amy wanted to be an actress and Ben wanted to direct films. He had a Super-8 camera constantly in his hand, shooting something or other.

“Ben, take it easy,” I told him. “You’re only eleven years old!”

He always chatted with me and Nipsey Russell, and he especially loved to hear Nipsey’s little raps:

I am a bachelor, and I will not marry

Until the right girl comes along.

But while I’m waiting, I don’t mind dating

Girls that I know are wrong.

Next thing I knew, little Ben was a regular on Saturday Night Live. After that, he was starring in movies like There’s Something About Mary and Meet the Parents, and also directing, like he always wanted. A few years ago, when Parade magazine asked him for his comedy inspirations, he named Robert Klein, George Carlin, and me. I was flattered and surprised. I had no idea he had been paying attention.

Ben grew up in the ’70s, watching the Golden Age of stand-up. But it was in the ’80s when stand-up truly exploded onto TV screens. All you needed for a TV series was a brick wall, twenty comics, and an audience. Producers taped everything, chopped it up—sometimes joke by joke, not even comic by comic—and, magically, they had a series of half-hour gangbangs, uh, I mean shows. They were everywhere, network, syndicated, and cable, on Showtime, HBO and Ha! (the predecessor to Comedy Central), from An Evening at the Improv and Comedy on the Road to Comic Strip: Live. I thought the phenomenon was great, and I was on many of those shows—multiple times too. What could be bad about comics getting more exposure?

Turned out there was a lot wrong. The good comics were on too much—familiarity breeds contempt. The bad comics were on too much—not being funny breeds contempt. Comedy clubs across the country suffered as well. People would not pay to see stand-ups when they could see them perform for free in the comfort of their own home. So by the end of the ’80s, clubs were going under.

What was a road comic supposed to do then? I returned to my first arena of professional show business—radio. Some twenty years after my only on-air gig in Norfolk, Virginia, I would once again have my own show. But it was politics, not comedy, that put me behind the mic.

I had written guest columns for the Los Angeles Times op-ed section explaining my thoughts on national and world events. Readers noticed them a

nd so too did various radio talk show hosts, mainly conservative ones, who invited me on their shows as a guest. Though I don’t call myself a conservative—we don’t agree on everything—obviously I am not a liberal. I was officially a Libertarian for a brief time, but they never win anything. I say I am a Logicist. I believe in logic and common sense.

On the air with folks like Rush Limbaugh, I talked about my belief in smaller government, personal responsibility, free-enterprise capitalism, and America in general. My opinions on race, not typical from a black man, really stirred the pot, everywhere from TV’s Politically Incorrect with Bill Maher to Bill O’Reilly and Sean Hannity on both radio and TV. I said that instead of our obsession with racism, blacks should focus on economic development. I said that the War on Poverty did little for the poor precisely because the bloated federal government was in charge. I slammed Jesse Jackson, Al Sharpton, and every other black leader who picked up a protest sign at the drop of a hat if it would get them on TV. Like me, many conservatives also emphasized the need for education and were tough on crime. I wasn’t afraid to say, even though I was a black man, that I agreed with them.

I taped the radio shows and sent them to people in the talk industry. Andrew Ashwood, probably the most insane man to ever program talk radio, contacted me. Most programmers are clean-cut, suit-and-tie, corporate types. Ashwood was different: He wore tie-dyed T-shirts; had a beard and long blond hair; smoked pipes, cigars, and cigarettes; drank in the studio; and was overweight and out of shape. He liked what he heard on my tapes and arranged a three-week try-out at WLS in Chicago, where I was partnered with someone else they were testing out, Roe Conn.

Our show was down and dirty, bashing, banging, talk radio. I trumpeted my support for the death penalty, especially for audiences who don’t laugh at my jokes. But I went further: I said I was all for bringing back public hangings. Every Sunday, in the park, bring the kids. Now that would be deterrence. Forget scared straight—that’s scared stiff.

But the station kept Conn, who became a fixture on Chicago radio, and released me. That did not deter Ashwood.

“Hey, man, heard the tape from LS,” he said. “Loved the liveliness. Fuckin’ great! You didn’t get hired, but fuck it, man—you were great!”

Later Ashwood was programming WOAI in San Antonio, Texas. He launched “The Great American Talk-off,” in which well-known people from across the country competed for the station’s early afternoon talk show slot. Fred Goldman, father of murder victim Ron Goldman in the O. J. case, was one of them. So was I. I didn’t win, but Ashwood thought highly enough of what I had done to make demo tapes of my performance and send them out to other programmers.

He pounded on Neil Nelkin, the program director at KKAR in Omaha, Nebraska, to hire me, and I was given a one-year contract. I moved to Omaha and was put in the same lineup with Limbaugh, O’Reilly, Dr. Laura, and Hannity.

The slogan for my show was “Give me an hour and I’ll give you the power.” Omaha is middle America, and I consider myself a mainstream American.

America is not perfect. We have made some bad decisions in the past and will continue to make some bad decisions. Nor is America the land of opportunity for everyone. I know a lot of people who have worked hard and been honest but have not succeeded—people who busted their asses and ended up homeless. They are like comics I saw at the Store who tried for years and never got on that stage. On the other hand, there are people who have achieved fame and fortune and never worked a day to deserve them. That’s life, and life is not always fair.

But I believe in America. This is a great country. Because we are free. I did not always appreciate that. You do not learn patriotism living in the projects. Once I got out into the world, met people who were different from me and worked with them, I grew to appreciate how you can make choices about your life. The choices do not always work out, but in America you have the freedom to choose—and you have the freedom to speak about your choice.

I pledge allegiance . . .

Michael Newdow of Elk Grove, California has periodically sued to have the Pledge of Allegiance banned from being recited in public schools because the phrase “under God” offends atheists.

The great thing about the freedoms Americans have is that Newdow has the right to leave this country anytime . . . unlike in Cuba. He also has the right to speak his mind . . . unlike in China. Okay, so he is offended by “under God.” But I bet doctor/lawyer Newdow won’t burn any of his American money because the phrase “In God We Trust” is printed on every bill.

I’m offended too, like when a pretty woman doesn’t give me the time of day. I’m offended when I get my tax bill. I’m offended by the prices at Starbucks. I’m offended by boy bands. But I get over it!

“I pledge allegiance to the flag of the United States of America and to the republic for which it stands, one nation under God, indivisible, with liberty and justice for all.”

If anyone is offended by that, then don’t say it. But you have no right to stop anyone else from saying it either. If “under God” ever becomes illegal, then call me an outlaw!

I strongly believe in the Constitution and the Bill of Rights—but as living documents. I am not a strict constructionist. I know this may come as a shock to some of my conservative friends, but the world has changed since the eighteenth century. Once upon a time blacks were declared to be three-fifths of a human being and women could not vote. America changes. We must deal with new realities.

Family values, for example, have changed. Comedians love politicians who trot out that photo of their smiling, happy family. We love speeches about family values—and they come from the mouths of liberals, conservatives, and everyone in between. Let’s get real, people. Marriage does not work for most people in the modern age. Marriage is a great concept, just like there should be no racial hatred and there should be no poor people. But most marriages end in failure, called divorce. The traditional family is no longer Ozzie and Harriet. Today, a mother and two kids is more traditional.

Marriage does not even work for gay people! For me, marriage is between a man and a woman, as it has been for, oh, all of human history. But gay marriage is here and is not going away. Gays have a rallying cry of “We’re here! We’re queer! Get used to it!” Even though I oppose gay marriage and, instead, support civil unions, they are right. So let’s not waste our time—the time of our government—trying to turn back the clock. Divorce will do for gay marriages what it has done for straight marriages—create millions more single-parent households.

I feel the same way about the new reality of illegal immigration. Illegal immigrants, mainly Latinos, are here and will continue to come here—and there is less and less we can do about it every day. There are already too many who have made it through. They have overwhelmed the system. The toothpaste is out of the tube and cannot be put back in. We acknowledge that we have failed every time we declare an amnesty.

At this point I say children should receive amnesty but not the adults who came in illegally. At least with children, they can be Americanized, including learning English. I love going to a fast-food restaurant and listening to three generations of Hispanic women at a table. The grandmother speaks to her grown-up daughter in Spanish. The daughter talks back in Spanish but then turns to her child and speaks English. I think we should all learn other languages, especially Spanish, but we live in America, and English is the language that has bound us together in the past and will in the future.

If nothing else, insisting on English being spoken is a statement that illegal immigrants ought to adapt to our country, not the other way around. Unlike the legal immigrants who arrived here in the early twentieth century, today’s illegal immigrants feel it is a right and not a privilege to be in America. Yes, the Statue of Liberty is inscribed with “Give me your tired, your poor / Your huddled masses yearning to breathe free.” But nowhere does that refer to illegal immigrants. Yet now that they have gained political power and can vote politicians in or out of offic

e, they are not going back.

The new number-one minority is Hispanics. Blacks had been the country’s largest minority since the 1600s. Now we can’t even hold that job!

Recently I learned about my own heritage. Most blacks in America are not raised knowing much about the generations who came before them. Many are afraid of what they suspect they will find—slavery.

I knew nothing about my father’s relatives. I knew only a little about my mother’s Perryman family further back than her generation—her and her sisters, such as Inez and Birdie Mae, and her brothers, among them Cornelius and Herbert. Fortunately, Cornelius Perryman has never been a common name for a black man born in Alabama. With my mother Lorena conveniently named for her mother and Cornelius for her father, my coauthor, Sal Manna, was able to trace that side of my family back nearly two hundred years.

I learned that my great-grandfather George was married in Dallas County, Alabama, in 1875 to my great-grandmother Ella. His parents, my great-great-grandparents, were a farmer also named George and a woman named Eliza. They had been born in South Carolina—he in 1818, she in 1822.

Because census documents prior to 1870 list only the sexes and ages of slaves, not their names, we do not know the whereabouts of great-great-grandfather George before that year. Upon emancipation, though, a majority of slaves took the surname of their previous owner, and a slave owner with a large plantation near where George lived was named Jeptha Vining Perryman. Perhaps he had been George’s master.

Dynomite!: Good Times, Bad Times, Our Times--A Memoir

Dynomite!: Good Times, Bad Times, Our Times--A Memoir