- Home

- Jimmie Walker

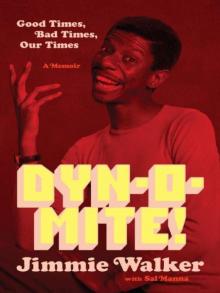

Dynomite!: Good Times, Bad Times, Our Times--A Memoir Page 23

Dynomite!: Good Times, Bad Times, Our Times--A Memoir Read online

Page 23

Three years later his smoking habit finally caught up with him, and the Greek was diagnosed with lung cancer. He moved out of his parents’ house and into an apartment. He told them not to call him. He said he would call once a week and if he did not, that probably meant he was dead. He no longer cared to live or for anyone to care whether he did or not.

A week went by without a call home. The police busted down the door to his apartment and found him dead.

The Greek was a great funny guy who could not catch a break. I only wish more people had the chance to really know him. Though a Lubetkin who jumps off a building to his death is memorialized, there are so many more talented people—like the Greek—who come to Hollywood but then leave as if they were never there at all.

The Greek’s obituary in the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette quoted, of all people, Leno. “He was what you would call a good old-fashioned joke writer,” Leno said. “He was like a joke machine. He could bang out a bunch of them. If you said, ‘I need jokes on Clinton hurting his knee,’ he could give you two pages. Some guys write topical or cerebral—he could’ve written jokes for Bob Hope.”

I was very unhappy reading that quote. At best it was hypocritical. Make no mistake about it—Leno could hire and fire whomever he wanted; he did not kill Steve Crantz. But he sure as hell didn’t show any heart. As one comedian has said to me privately: “Jay Leno will show up at your funeral, but he’ll be the reason you died.”

The Crantz episode was not an isolated situation either. Bob Shaw, Leno’s old partner from his Boston days and the comic whose poverty helped instigate the Great Comedy Strike, was another funny guy who never received his just due. At one point he fell ill and needed a couple of shots to qualify for the performing union’s insurance plan. Boosler called Leno and asked him to book Shaw for the two shots. Why not? Shaw was his friend! Leno passed. Boosler went ballistic and never forgave Jay. Fortunately, Shaw eventually became a writer on Seinfeld. He also cowrote A Bug’s Life.

Only when Leno began guest hosting the Tonight Show on Mondays did Helen express any genuine confidence in him—because he became her chance to land the biggest prize in television. But for Leno to take over the Tonight Show she would have to push Carson off his throne: No one knew when Johnny wanted to step down. Besides, everyone expected Letterman, his favorite, to be his successor someday. After all, he was doing his own successful show right after Carson, and Johnny clearly had anointed him.

Helen had a plan. I know that because she told me what she had in mind. I tried to dissuade her, saying it would be “suicide” for Leno to stab Carson in the back. When I brought up Letterman’s widely accepted right of succession, she said, “Fuck Letterman! We’ll kill his show!” There was nothing anyone could do to stop her.

Her scheme included doing a complete makeover on Leno. She had him cut his hair and she put him in suits. No longer would he drive to the studio on his motorcycle. When Jay was on the road, he would visit the NBC affiliates and make friends. When he was in LA, he would glad-hand the press and praise Johnny. She also stopped him from doing the Letterman show in New York, which did not sit well with Dave. When I appeared on Letterman’s show, producer Bob Morton begged me to call Jay and ask him to do the show again. But nothing I said would help.

That Letterman appearance was the legendary show with guest Shirley MacLaine. Dave wanted to have fun talking about her past lives. She did not and said “maybe Cher was right, maybe you are an asshole.” Dave was so shocked that even he struggled to joke his way out of the awkward situation. When the segment ended, Shirley refused to shake his hand. After the commercial break, I came on.

My first line was “I was so happy Shirley MacLaine was here. I talked to her and we found out that in one of her previous lives I was one of her slaves!” It killed. Dave laughed, easing the tension, thank you very much.

Meanwhile, behind the scenes Helen was at work trying to oust Johnny. Among her tactics was to ask certain hipper guests to perform only on the Tonight Show when Jay was hosting. If they crossed her, she threatened that they would never appear on the show again. She also planted stories in the entertainment trade magazines about Carson being out of date, about NBC wanting him to retire sooner rather than later, and about Leno being the network’s desired successor. Then she arranged for a February 1991 story in the New York Post that laid all of that out for the public for the first time. Carson was made to look feeble and impotent, and he was embarrassed. Finally, in May, Carson announced that he would retire the following year.

Leno—not Letterman—took over the Tonight Show. Author Bill Knoedelseder said it best: “Given the opportunity, most—if not all—of them [his fellow comics] would have done what Leno did, but they probably would have felt worse about doing it. Nobody blamed Jay, but everyone understood why Dave felt betrayed.”

Helen became the executive producer of the Tonight Show with Jay Leno. As part of the deal the Kushnicks sold to NBC their management company, which largely consisted of clients I had brought in many years earlier—dominated now by Leno, who I had fought to keep her from dropping. The price tag was $7 million. When I finally revealed to Leno how Helen had forced me from my own company years earlier, he refused to believe it, felt I was slandering her. He told Helen what I had said, and she banned me from the Tonight Show.

I wasn’t the only one. Helen made it known that if any guest appeared on Letterman’s show or anywhere else when she wanted them, they would not be welcome on the Tonight Show with Jay Leno. Helen vowed to bury both Letterman and Arsenio, who foolishly boasted that he would “kick Jay’s ass” in the ratings. She launched a Hollywood reign of terror. Agents and managers were downright frightened, but they kept the prohibition quiet.

Then country singer Travis Tritt was booked to do Arsenio. The Tonight Show also wanted Tritt—and on a date before his Arsenio appearance. Tritt’s manager, Kenny Kragen, tried to accommodate Helen, but in the end he had committed Tritt to Arsenio first and felt he had to stand by his word. Helen went berserk, saying she would never speak with Kragen again and slammed the phone down. According to author Bill Carter in The Late Shift, Helen’s office then called Kragen back within half an hour and canceled an upcoming appearance by another of his clients, Trisha Yearwood.

To most power brokers in Hollywood Helen wielded a big stick. If you crossed her, you could be dead in the water. As a matter of fact, that is what she would yell: “You are dead!” But Kragen, the man behind the “We Are the World” and Hands Across America antihunger benefits, had enormous credibility and respect throughout Hollywood. He also had guts and integrity. Helen had not figured on Kragen deciding that enough was enough. He went public in the Los Angeles Times about what was going on. The floodgates opened with revelations about Helen’s vindictive style running the Tonight Show. The backlash against her was fierce.

NBC, who was not happy with her anyway, began to move to force her out. On Howard Stern’s radio show, Helen charged that she was being picked on because she was a woman and threatened to sue the network for sexual discrimination. Apparently she felt she held the trump card—Leno. If she was purged, she would take Leno with her.

She did not realize what those of us in comedy circles already knew—Leno would do whatever was good for Leno. Helen was fired. Jay kept his job.

Soon after, Helen was diagnosed with breast cancer and had to have a mastectomy. To show how despised she was, a “joke” made the rounds among comedians: “She’s alright, she still has her dick.” Like I said before, comedians can be tough.

With Helen no longer in charge, Leno agreed to have me on his Tonight Show. But he still spoke with her, and her antipathy toward me made him refuse to work with me on my shot, like he had done many times before when I appeared on Carson or Letterman. This time I would have to go over my shot not with him but with Jimmy Brogan, who had become his right-hand man and comedy coordinator. I had helped Brogan get the gig as one of the regular emcees at the Comedy Store when he was on my sta

ff. Now he was doing for Leno what Mister Geno and then Brogan himself had done for me back in the day.

“You can’t do the Jeffrey Dahmer line,” Brogan said after looking over the jokes I had planned. Dahmer was a notorious serial killer who, at the time, was incarcerated for several gruesome cannibalistic murders. Also at that time another convicted murderer was about to be executed, again sparking a debate about capital punishment, and I had an oh-so-topical joke that connected the two killers.

“Why can’t I do the joke?” I asked Brogan.

“Jay doesn’t like Jeffrey Dahmer jokes.”

“What are you talking about?” I said. “Jay does Dahmer jokes all the time!”

Later that day it was showtime. I went into my shot. The audience was laughing, the band was laughing. I was rolling at breakneck speed. The spot came for the Dahmer joke and I did it:

All this talk about capital punishment, about whether the electric chair is humane, about lethal injections being humane. I have an idea that’ll make everybody happy: If you want to get rid of a murderer, you rub barbecue sauce on him and put him in a cell with Jeffrey Dahmer.

Excuse the expression, but the joke killed.

I looked out the corner of my eye at Leno at his desk. He was not laughing. He was not happy.

I finished my shot and walked to the couch. Leno did not shake my hand. He said, “Jimmie Walker. We’ll be right back.” During the commercial break he told me, “You had to do the Dahmer joke.”

“Didn’t it kill?”

“That’s not the point.”

When we came back on the air, we did a couple more jokes and then we were finished. Jay was still not over it, saying, “The point is I asked you not to do the line and you did the line.”

My point was that funny mattered. Even Branford Marsalis, then the bandleader, came to my dressing room and said my shot was the funniest he had heard on the show to date.

Here’s the kicker: A couple weeks later Leno was quoted in a national magazine with a joke about Dahmer. It was my joke! I was shocked. When I called him to talk about it, his staff referred me to Brogan. I have not been on the Tonight Show since. When I have seen him in passing, Ray Peno says, “Brother Walker,” and imitates a bit in my act where I go, “Well, well, well.” That’s all.

Stand-up comics are a brotherhood. We have seen each other bomb, seen each other helpless on stage, seen each other at our worst. So when we have a chance, we give each other a hand. What I am most proud of in my entire career is not what I have done but that I helped out “my guys”—Letterman, Leno, Frank ’n’ Stein, Louie Anderson, and all the others.

Once upon a time all of my guys wondered if they were good enough, if they had a chance to make it in this business. An actor can get by without being dramatic. If a comedian isn’t funny, then he’s not a comedian. They were funny, but a lot of folks come to Hollywood with talent and never succeed. I have seen many great comics who never made it. There was no rhyme or reason or logic why they didn’t—except luck did not come their way. Maybe my guys would have hit the big time without me being around. But it makes me happy to think that when they needed a hand, I was there for them.

I have continued to do that with my opening acts, becoming for them what David Brenner was for me. Dustin Ybarra, a Hispanic kid from Texas, was seventeen when he opened for me in Dallas a few years ago. He was very talented, but he was raw. Sure, he was big in Dallas and all his friends and fans laughed at his jokes, but he had to get among other comics, compete with them, grow that thick skin, make himself better. I took him under my wing and helped him move to New York and get an agent. As the song goes: If you can make it in New York, you can make it anywhere.

The world is going to end in 2012. That’s what they say. I’m kind of hoping that it does. Cause I’ve got this couch from Rent-a-Center. No payments until 2012. That’s a free couch right there! The guy said, “You know you’ve got to pay in 2012.” I said, “Bro, we’re all going to pay in 2012!” (Dustin Ybarra)

I’m glad I don’t go to school now. Bullies are so mean. Now they kick your ass and put it on YouTube. You go home and your parents already know you got your ass kicked. You walk in like, “Mom . . .” She goes, “I know, sweetie, ‘Fat Kid Cries’ got forty-two thousand hits. Your ass-whomping went viral. Congratulations!” (Dustin Ybarra)

He took my advice, and, with material like that, before long he was getting spots around town. A couple of MTV pilots followed, then Live at Gotham, and now he is in major films.

Jay has had the opportunity to help those who had helped him as well as encourage and develop a new generation of comics. He was made the keeper of the franchise, the Tonight Show of Jerry Lester, Steve Allen, Jack Paar, and Johnny Carson. Along with Letterman, Merv Griffin, Mike Douglas, and others, they helped launch and support the careers of so many comedians. That the same cannot be said for Leno is a shame. He abandoned the stand-up comic. That is not just my indictment; that is the widespread belief in the comedy community.

An exasperated Boosler once asked me about Leno: “What does he think? That the one with the most toys wins?”

“Yes, Elayne,” I said. “He does.”

No one begrudged Leno his success. What was expected, however, was that he would help other comics, whether behind the scenes with the Greek or on his stage for Bob Shaw or some unknown stand-up needing his first shot. When he closed out his first Tonight Show run in 2009, he said that sixty-eight children had been born to his staff since 1992. Too bad he couldn’t also say he had brought a new major stand-up comic into the world during that time. Instead, in now some twenty years of hosting his own show, he has not broken a single significant stand-up act, which is amazing given the reach of the Tonight Show. The only comedy career he has launched has been that of Ross Mathews, who is more of a personality than a stand-up.

However, Chelsea Handler and her Chelsea Lately show has been a tremendous platform for comics—Whitney Cummings, Natasha Leg-gero, Jo Koy, Josh Wolf, Heather McDonald, Sarah Colonna, Loni Love, and Kevin Hart, just to name a few. There are radio shows that have done a better job than Ray Peno at providing a stage for comics. Howard Stern can take some credit for Sam Kinison and a lot more for Greg Fitzsimmons and Artie Lange. Bob and Tom helped Frank Caliendo as well as Larry the Cable Guy, Bill Engvall, and Ron White from the Blue Collar Comedy Tour. Opie and Anthony brought Jim Norton to the forefront. Some have appeared on Leno’s show but only after achieving their breakthroughs elsewhere.

Ironically, the most popular comic Letterman launched was Leno. But within the comedy community there have been so many more that he has helped, including nearly everyone from his early days at the Store, from Johnny Dark, Tom Dreesen, Richard Lewis, Jeff Altman, and Johnny Witherspoon to George Miller and a road comic named Jimmie Walker.

Designer colognes . . . they got Obsession, they got Passion. Now they’ve got a cologne for black men only, called Repossession—for the black man who thought he had everything, but it didn’t work out that way. (Jimmie Walker, Late Show with David Letterman, 1995 or 1996)

Letterman is not a “people person.” Neither am I. Neither was George Miller, who in the early days roomed with Dave. Letterman and George became the closest of friends, and the three of us always got along. George and I traveled across America playing so many shows together.

When George was diagnosed with leukemia, Letterman made sure he was booked on his show enough times so he would qualify for his union health benefits (he would appear fifty-six times over two decades). When his condition worsened, Dave donated a million dollars to put him into an experimental medical program at UCLA. It saved his life for a while. And when George said, “I don’t want to sit around and wait to die. I want to work,” Letterman came through for him again.

He rarely called his agents at Creative Artists Agency (CAA), but for George he would do anything.

“Yes sir, Mr. Letterman, what can we do for you?”

Letterman proposed a tour calle

d Classic Comics of Late Night, starring four old friends—George, Bobby Kelton, Gary Mule Deer, and myself. He told CAA he wanted the agency to book us into casinos and theaters around the country.

Miller, Kelton, Mule Deer, and Walker?

They told him, “We’re agents, not God!” They could not book the tour.

What Letterman did next has never before been revealed: He paid the freight himself—paid for the whole tour. When a show did not sellout, he bought the remaining tickets and had them given away. We played about twenty dates—the Foxwoods and Mohegan Sun casinos in Connecticut, Emerald Island casino in Nevada, Cerritos Performing Arts Center in Southern California, and elsewhere. We traveled first class and stayed at first-class hotels, and it was a great show too. Letterman did that for George.

Kelton had no idea what was going on; he thought we really were selling out. When Dave found out I told Kelton the truth about the tour, he was very upset with me. He didn’t want everyone to know. He’s that kind of guy. He will probably be pissed reading this now.

One day George and I were driving to a gig in Washington and we passed a cemetery. As if it was the most ordinary thing, George said, “Oh, that’s where I’m going to put my ashes.” The last thing he ever said to me was “You’re gonna miss me when I’m dead!”

He worked until his last day. In March 2003 he collapsed in his hotel room at the Riviera in Vegas and was rushed to a hospital. I received an e-mail from Boosler saying, “Hi. How’s your day going? Oh, by the way, George Miller died.”

His memorial service at the Laugh Factory has gained legendary status. Assembled were Richard Lewis, Dreesen, Boosler, Mort Sahl, Johnny Dark, Charlie Hill, Kelly Monteith, myself, and many others. Of course, Leno showed up too. Letterman was unable to attend because he was dealing with his own medical condition at the time—shingles. Given the nasty breakup between Leno and Letterman, many of the comedians in attendance were grateful that a potential scene of discomfort and awkwardness was avoided.

Dynomite!: Good Times, Bad Times, Our Times--A Memoir

Dynomite!: Good Times, Bad Times, Our Times--A Memoir