- Home

- Jimmie Walker

Dynomite!: Good Times, Bad Times, Our Times--A Memoir Page 8

Dynomite!: Good Times, Bad Times, Our Times--A Memoir Read online

Page 8

Miles Davis was coming to the Cellar Door after the release of his classic Bitches Brew album. Miles was a revered jazz musician, but he was notoriously unpredictable. I might have to do as much as fifty minutes before he would go on.

The room was packed for every show, mainly with adoring fans from the area’s colleges. I would tell my jokes and wait to hear a clap from the wings to let me know Miles was ready. Sometimes he would stand outside the club smoking a cigarette or just stay in his dressing room. In the meantime I had to keep going, getting into audience participation—“So where are you from?”—when I was out of material. When I finally heard the clap, I would get off stage.

Sadly for his fans, Miles played his trumpet balls to the walls on only a few of the ten or more shows. For the others he messed around for half the show, maybe played a little piano, and cut his set short. His great band—Wayne Shorter on soprano sax, Joe Zawinul on electric piano and Billy Cobham on drums—did the heavy lifting. Many of his fans, who treated him like a god, left disappointed.

Because I was doing more time, I of course asked Jack for more money.

“Fat Jack,” I said, knowing he hated to be called that, “I need $600 a week.”

“You’re not worth it.”

“One day I’m going to come back and record an album here,” I told him. “I won’t be a ‘nobody’ then.”

“Yeah, right.”

Some of the clubs I played were not, well, legal. They existed for only one night, and the locations—usually an abandoned warehouse or loft on the West Side—could only be discovered through flyers or word of mouth. Yet hundreds of people would show up at about one in the morning. Years later they were called raves, but we referred to them as after-hours clubs.

They had a disc jockey and disco dancing, and at around 4 a.m. the music stopped and they brought on a comedian. I would walk into the middle of the floor—no stage—and do at least half an hour. The purpose was less entertainment than to give the promoter time to sell more drinks, all of which were very expensive. The break also gave the promoter time to begin packing up. When the “club” closed, he wanted to get out of there as quickly as possible, just in case the police finally showed up.

Sometimes the comic would not last half an hour. The sweaty, drunk, sex-charged crowd was not in the best mood to hear jokes at 4 a.m. They would boo and shout for you to “get the hell off” so they could crank up the music again. Only two of us were actually good at these gigs—me and Freddie Prinze. We were younger and hipper than most of the other comics, and we could interact with the multicultural crowd better than they could. We played it loose, brother.

When we finished, the dance would continue for another two hours, until usually right around sunrise. Unless the police arrived, in which case I quietly walked away as if I had stumbled onto the place by accident—never look like you are scared. That was good advice for a comic struggling on stage too. Another lesson learned was to get your money before you went on because the dude with the money might not be there at the end.

Like me, Freddie had tremendous confidence. He came from the middle-class Washington Heights area and had boundless energy. He was only seventeen years old, but he believed he was the best comic in the world. His real last name was Pruetzel and he wanted to change it to King because he wanted to be known as the King of Comedy. But Alan King already had that surname, so he chose Prinze, as in the Prince of Comedy.

I don’t remember the moment I met Freddie, but I do remember what it was like every moment I was around him. He was electric. There was always something going on with him that was different from other people. He was a rarity. At the same time that he had an in-your-face attitude, he was so good looking and charming that you could not help but like him. He reminded me of Muhammad Ali, who would talk shit about knocking out his opponent but be so funny about it that you could not help but enjoy him.

I’m leaving my bedroom late at night to go into the kitchen. A roach says to me, “Hey, Freddie, where you goin’, man? Hey, you don’ bring back some potato chips, we shut the door on you, man!”

Somehow Freddie made that joke work. He had enough chutzpah to get on stage and do forty-five minutes despite having almost no act. Besides a catchphrase—“Looking good!”—all he had was his Hungar-ican routine about being part Hungarian and part Puerto Rican. Even that was sketchy. He was hardly Hispanic from a cultural standpoint. But it was a lot easier to make jokes about Hispanics than about his Jewish Hungarian father. One of my favorites:

My mother’s always talking about her wedding. “You shoulda been there,” she says. She doesn’t remember. I was there, and so were my two brothers.

Freddie had no problem telling you how talented he was or how successful he was with the ladies. One night at the Camelot, he boasted, “I can get as many women as I want.”

“How many?” Brenner asked.

“I can get at least five in one night.”

“Wanna make a bet on that?” Brenner asked.

“Absolutely,” Freddie said.

Brenner, Landesberg, a few others, and I took him up on the wager. We used Brenner’s pad because his building had a doorman who could keep count for us. The next night, along with Freddie, we made our rounds of the showcase clubs. At about two o’clock in the morning we met up at the Camelot. Except no Freddie. At 3 a.m. we rolled up to Brenner’s apartment and asked the doorman how many women had been in the apartment with Freddie. He told us that Freddie had been going in and out—with nine different women! In one night! He was a piece of work.

Lenny Bruce was a favorite of his, and he and I would listen to his records for hours. Coincidentally, one of those albums was put out by Alan Douglas and his Douglas Records, which released the first album from the Last Poets. We had every book about Lenny too. We would discuss everything about him. We lived, breathed, talked, and studied comedy, but especially anything Lenny. We were hooked on the guy because he just seemed to be so important, so different for his time, and we wanted to tap into that energy.

When I listen to his albums now, the material sounds to me to be more rant than comedy. From Klein and Brenner, I learned to be more succinct. They had more refined pieces, with a beginning, middle, and end, because they were writing for TV shots. Lenny rambled like a nightclub comic. He was inflammatory and controversial, which made him a hero to most comics, including me and Freddie. But we were very different in style from him.

Strangely, Freddie became intimate with Kitty Bruce, Lenny’s daughter. She worked at the Improv as a coat-check girl and went crazy over him. She loved Freddie. “You are the first comic to make me laugh since my father,” she told him. Freddie, as expected, quickly took her to bed. Whenever he screwed her, he would come back to us and say excitedly, “It’s like Lenny is watching us!” After we all moved to LA he told me that he made love to her on the grave of Lenny “Bruce” Schneider at Eden Memorial Park in Mission Hills—and that during the act he heard Lenny rooting him on: “Go man, fuck her! Fuck her!”

I had my first serious relationship with a woman I met at the Improv. Leah came up after a show and we started a friendship. She was about ten years older than me, had a master’s degree in history or literature, and was extremely smart. She was a substitute teacher, did temp office work, and wrote articles and poetry, though she never sold any of it. She was very much into authors—from Shakespeare to Jack Kerouac to LeRoi Jones (aka Amiri Baraka). She introduced me to their writing and that of others. She was like a character out of a Woody Allen movie, except she lived on the West Side of Manhattan instead of the Upper East Side. But I didn’t think of her in romantic terms, despite her great legs, because she was white. She was simply a friend who was supportive of my comedy career. She would type up my material and, because she was one of the few people I knew in the city who had a car, sometimes drive me wherever I had to go.

Finally it dawned on me that she wanted a more physical relationship. But I did not want to go out with or be seen wit

h a white woman. I had just come from working with the Black Panthers and was very much into my antiwhite bag. I did not want a white girlfriend.

I told Brenner about my problem.

“I’ve gone out with all races and religions,” he said. “When the lights are out and you’re under the sheets, a woman is a woman. Just go for it!”

Three or four months passed before Leah and I went to bed. But I still felt uncomfortable. She was terrific to me—totally devoted—and I knew she was happy with our relationship. I, however, was not so devoted and did not treat her as well as I should have, emotionally speaking. I always had an excuse: “You’re white. You don’t understand.” Having seen what my father did to my mother made me want to treat women decently. But that does not mean I knew how to have a relationship. Leah was my teacher in many ways, but inevitably, we grew apart.

Barbara was the polar opposite of Leah except that she was also white—Leah had forever broken that taboo for me. Barbara was aggressive and tough. She was not sweet; she was cocky as hell. I met her at a comedy club in Greenwich Village, and she looked like a young woman from the Village—tall, slim, and brunette, like a Joan Baez. She played a little guitar, sang a little, painted and sculpted a little, and had come to the city from upstate to get into show business. She was opinionated about everything. She would even be critical of what I did on stage. But if someone else said something negative, she would defend me with everything she had. Other comics would ask, “Who’s that chick? She got into a beef at the bar with some people about you.” Later she would tell me, “You know, you sucked tonight.”

By this time the other woman in my life, my mom, had become a nurse. She worked her way up in the field, became a registered nurse, and then went to college and earned a master’s degree. Eventually she was appointed the head of nursing at Montefiore Hospital in the Bronx. I’m just a comedian; my mother is the one who deserves to have a book written about her. She never complained, and she achieved so much.

She remarried—a really nice guy named William Boyce, who she met at church. A small, round man, Mr. Boyce was supposedly one of the first black guys in the laborer’s union. He loved my mother very much, but she never seemed very close or affectionate to him. Maybe it was a marriage of financial convenience for her. There were times I felt my mom stayed late at her job because she didn’t want to come home to him. She still loved my father.

My career was also advancing. When Time magazine wrote that I was “one of the finest black comics in the country,” Budd framed the article and put it up on a wall at the Improv. The club had become a major magnet for aspiring stand-up comedians.

One hopeful would drive down from Boston to work out at the Improv whenever he was in town delivering a Rolls-Royce or other expensive auto for his day job at a foreign car dealership—Jay Leno. In turn, whenever any of us were in Boston, we used a crash pad he had that we called the Leno Arms. There wasn’t much more than mattresses on the floor, and I don’t even think there was a lock on the door. Every now and then Leno’s mom and some of her friends came from Andover with buckets of disinfectant and cleaned up the place. When I landed the Playboy Club circuit—which was pretty classy—and played the one in Boston or was booked at the far less classy Sugar Shack in the infamous Combat Zone, I stayed at the Leno Arms.

Freddie also stayed there. Fascinated by guns, once he was showing off his latest purchase and all of a sudden the pistol fired—blew a hole in the ceiling of the Leno Arms. That hole was still there when Leno moved out of the place.

At the time nearly all of the major TV talk shows came out of New York—Johnny Carson, Merv Griffin, Dick Cavett, David Frost. Even Jack Paar, a late-night giant in the ’60s who hosted the Tonight Show before Carson, was making a comeback on network TV in the early’70s. But every comic’s goal was to get on the Tonight Show with Carson. His show could launch a career. All of my comic friends, including those who would never make it big, had by now appeared on one or more of those shows—but not me.

My first TV experience was on Joe Franklin’s local show on WOR. He had been doing it for twenty years and was already a cult figure. Not only did everyone come on his show—from Marilyn Monroe to John Lennon—but anyone could get on, even me: “Big, big things for this young man. Lots of talk about him. Lots of chatter. Very funny. On the upswing. Jimmie Walker, ladies and gentlemen. Funny young man. See him at the Improvisation.”

Franklin also staged a regular live showcase at Brickman’s resort in the Catskills. If you did well, you might land a paying gig at one of the other major resorts, such as Grossinger’s or Brown’s, which catered to Jewish crowds. I had performed at so many community halls and bar mitzvahs that I was comfortable bringing out my Jewish material.

I would open with: “I bet you’re surprised to see a schvartze up here.” That would always get a big laugh and break the ice. “You know, maybe you can relate to this—my mother got upset with me because she heard I was going out with a shiksa.”

Not that they would always understand my jokes. I had a bit that started with “I saw this graffiti the other day,” and an older woman in the front row turned to a friend and asked loud enough for me and the rest of the audience to hear, “What’s graffiti?”

When Brenner became a regular guest on the Mike Douglas Show, which taped in his hometown of Philly, he put in a good word for me. After weeks of needling producer Ernie DiMassa and talent coordinator Vince Calandra (who had the same job for Ed Sullivan when the Beatles were booked), he finagled me an audition. In front of an audience of about forty people, all of whom were also auditioning, I did a great set—killed, destruction, even with the hard-nosed show biz crowd.

Went to an all-black school. Put on a production of Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs. The dwarfs were black. We had to bus in Snow White.

When I got back to the Improv, Brenner asked how it went. I said, “I think it went well but no one’s called.” He phoned DiMassa and asked what was up. DiMassa told him, “Yes, he was funny. But he’s too black.”

Brenner answered, “Yes, Ernie, that’s because he IS black!”

Compared to others in comedy at the time, I was too black. Even with smoothing out my material and attitude from my Last Poets days, I was too caustic for mainstream TV. I also looked younger than nearly any other comic besides Freddie—I didn’t even wear a suit and tie on stage. The only comic around who was younger and blacker was Franklin Ajaye, who was far more political and scared the TV folks more than even Pryor did. One of my favorite jokes from him was:

These police will arrest you for anything. I was in LA the other day with a friend and they arrested us for being two niggers on a sunny day. We were guilty!

I wasn’t jealous of the others getting on national TV. I was happy for them. We were friends. When one of them scored, it was a celebration for all of us. We would go down to the tapings and sit in the audience to root them on. I figured my turn would come—someday. Brenner never stopped encouraging me: “Don’t worry, you’ll get on. I’ll push for you.”

Being young, black, and cool was an advantage in getting one sort of job though. I met a woman who worked for Columbia Records, which was run by Clive Davis, and she asked if I would emcee at a signing party at Max’s Kansas City on Park Avenue South for one of the label’s new artists. “A hundred dollars? Sure,” I said.

Five guys walked on stage. They wore what we then called braids but later knew as dreadlocks. A haze of pungent smoke surrounded them, which I recognized as weed, but they called ganja. They played a style of music few people had really ever heard before—reggae. When the band finished, the crowd was stunned; no one applauded. No one knew what to think of what they had just seen and heard. Only when Clive jumped on stage and said, “Aren’t they great!” was there cheering. Obviously Columbia in 1972 was not the place for Bob Marley and the Wailers.

There was a better reaction for a guy from Jersey by the name of Bruce Springsteen. His performance was so amazing that the crow

d of jaded music-industry types insisted on an encore. That was strong. But Springsteen was not my style. I was more excited when Columbia signed Earth, Wind & Fire and I performed at their signing party. I could not have known it at the time, but Marley, Springsteen, and Earth, Wind & Fire would all get into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame.

Finally, one night at the Improv Brenner accosted Tom O’Malley, the talent coordinator for Jack Paar Tonite.

“Hey, how about Jimmie Walker for your show?”

“I don’t like him,” O’Malley said. “He’s too angry.”

Nevertheless, Brenner persisted and arranged an audition. When I arrived at their offices, I was sent to a sterile room with only one person—not O’Malley—sitting in a chair behind a desk and eating a sandwich from the Stage Deli. His name was Hal Gurnee, and he had directed the Tonight Show in the Paar era and now was back with him.

I said, “Hi, I’m . . . ”

He interrupted. “I know who you are. You’re that Jimmie Walker guy everyone’s been talking about around here.”

“Okay,” I said, surprised.

“Yeah, people tell us you’re a pain in the ass.”

“Oh,” I said. “So are we going to do the audition?”

“Let’s do it.”

“Where? Aren’t we going downstairs to the studio—where there’s an audience?”

“No,” he said. “Just do your bit right here. I’ve been in this business a long time. I know what’s funny.”

There is probably nothing harder for a comic than to perform for an audience of one. Laughter being contagious is a comic’s best friend. But I had no choice.

I was about three minutes into my routine when he stopped me.

“That’s enough.”

Damn, I had failed, I thought.

“Can you do the show tonight?” he asked.

“Uh, yeah!”

“Okay, be back at five-thirty. See you then.”

My reaction was less “Wow!” than “About time!” I felt I deserved this chance. I had been mentally preparing for my TV debut for more than a year. Brenner, our ringleader, had been on Carson, Griffin, Douglas, and Sullivan, and he would constantly talk about what he had done and what he was about to do. So when you finally did get on a show, you already knew what was going to happen and what you needed to do.

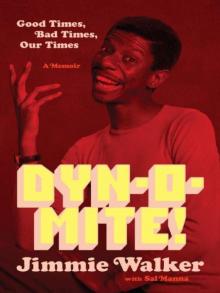

Dynomite!: Good Times, Bad Times, Our Times--A Memoir

Dynomite!: Good Times, Bad Times, Our Times--A Memoir