- Home

- Jimmie Walker

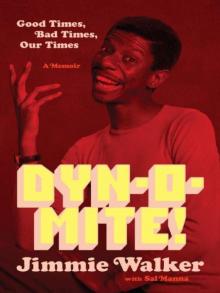

Dynomite!: Good Times, Bad Times, Our Times--A Memoir Page 13

Dynomite!: Good Times, Bad Times, Our Times--A Memoir Read online

Page 13

Most of all, he deeply missed his family. After he was in LA a few months I took a call from his dad. He told me that Steve was afraid to tell me that he had moved back to Pittsburgh the previous day. Steve wanted me to know that he had left the keys to the car in the apartment and that the door was unlocked. Obviously, Crantz and LA were not a match. When I finally talked to Steve, he wondered if it would be okay if he sent me jokes once in a while. I said, “Of course.”

Along with traditional comedy writers like Crantz, I wanted wildman comics like Allan Stephan, Jeff Stein, and Mitch Walters at the meetings. I needed to hear that voice of craziness, people who would break the rules, even mine.

A couple of oddball Jeff Stein jokes (dates unknown):

I travel a lot . . . tried to save some money . . . took one of those no-frills airline flights. It was terrible—they made me row!

I meet some strange girls. I asked a girl out the other night and she asked if she could bring a friend. I said, “Sure.” She brought her probation officer.

I needed to hear what was wrong for me, too outlandish for me, so I knew not to go there. Allowing that spectrum in a meeting was important because if I didn’t, I would never know what was being done on the sharp edges of comedy, even if that was not a place I wanted to go. I also needed a voice of reason in the room, like Mister Geno or, later, Jimmy Brogan, who understood comedy and I could trust to say to a writer, “Love that but, really, no.”

We worked at my house until about seven-thirty or eight at night. Then Mister Geno and I would roll over to the Store. On the way we decided which jokes to test out on stage. Mister Geno had a copy of them and would check them off as I tried them. If the audience liked the joke, he put a check mark next to it. If it flopped, he put an “X” next to it. I almost always taped my shows too. Later, we would go over the tape, analyze the audience responses, and work on changes. My rule has been that if a joke does not work three times, I take it out—no matter how much I personally like it. There are some comics who say, “To hell with the audience, what do they know?” But I believe you have to be true to yourself and you have to listen to your audience.

I thought I already had a good work ethic, taught to me by comics such as Brenner. But watching Lear control as many sitcoms as he was—as many as eight in one season—was inspirational. I learned from him never to be satisfied with a performance, never “phone it in.” Lear told me, “Don’t rest on your laurels. Don’t just show up to pick up the dough.” To this day I tape the late-night talk shows every night to see what the new comics are doing and what topics people are talking about. I am not beyond learning something new.

The best jokes from my writers were collected into “chunks” arranged by subject and were ready for any television appearance or major gig. When I appeared on a TV show and did my stand-up, they would tune in to see if any of their jokes made the cut. If none of them did, they would not be happy. When they heard someone else’s joke, they would shout at the TV, “That’s bullshit! My joke was better than that!” Then they would come to a meeting and ask, “When are you going to use my joke?” I’d say, “I’m getting to it, man.”

A joke might experience so many changes in meetings or afterward that in the end you could not decipher the original source. All I know about the following joke was that it came out of a March 3, 1976 session with me, Wayne, Jay, Byron, and Dave:

You all into that astrology stuff? Some girls really believe that their lives are controlled by the planets. This fat girl told me the reason she ate so much was because her moon was in the house of Mercury. Looked more like it had been in the International House of Pancakes.

Maybe no one wanted to take credit for that one. But with such talent in that room, there were more hits than misses. Some of the uncredited jokes that earned check marks:

Kids always say they’re seven and a half, eight and a half—always fighting for those halves. As you get older, you stop fighting for those halves, like you never hear adults say, “Yes, I’m forty-nine and a half.”

The government just did a study. Found out the reason the unemployment rate is so high is because there are so many people out of work.

Went to the doctor. Had to get an X-ray. Just before the technician took the X-ray he ran behind the screen with me. Said he wanted to be in the picture too.

There’s a new course they have in school now called Black Studies. But I always wondered what would happen if I flunked. Would I fade?

An article in Cosmopolitan says that women can tell a man’s sexual prowess by the kind of plants he grows. I’m taking no chances; I have a redwood growing in my bedroom.

I was on the Johnny Carson show last week and I mentioned in passing that I had never gone out with an airline stewardess or Playboy Bunny before, and I do not believe the response I got. I got like two hundred letters from guys who said they’ve never been out with one either.

There is one place, however, where even the greatest jokes ever told do not stand a chance—on stage before a rock concert. No one was bigger during his heyday than rock star Peter Frampton, who hit in 1976 with “Baby, I Love Your Way,” “Do You Feel Like We Do” and “Show Me the Way,” when his folks invited me to open for three upcoming dates.

For the first one there were four thousand fans waiting for him at an outdoor amphitheater in New Jersey. The old line about rock fans at a concert is true: They had their drugs timed for the act they wanted to see—and I was not that act. All they knew was that I was the guy keeping them from seeing Frampton. The reaction was harsh. People were yelling, throwing things—pissed off. They kept screaming for Frampton. I finally yelled out, “Anybody have VD?” They all cheered. After a few minutes I walked off the stage feeling like I had been flushed down a toilet, driven through the sewer system, and dumped into the Hudson River.

The Frampton people still wanted me to do the next date! We flew charter to Vancouver, Canada. This time there were fifty thousand fans waiting at a football stadium. Again, nothing good happened for me. I told them I could not do the third date and flew back to New York.

Sometimes not even a staff of writers can help. Many years after Good Times I opened at the Hilton in Las Vegas for Gladys Knight, which I had done many, many times before. I went on stage for the first performance of an eight-night run and did my jokes. The audience was so quiet I could hear the air conditioner blowing. The next day I got an absolutely horrendous review. The writer was not wrong, because there were no laughs the night he was there. I was so unnerved that, before the weekend dates, I flew in some of my writers, including Mister Geno. They watched a show. Once again there were no laughs.

They were as confused as I was. “But these jokes work!” they said. They had no answer. Mister Geno and I resorted to picking up a few joke books and old comedy albums to adapt a few of their jokes. That helped a little, but I still ate it. I never knew why. The next shows I did elsewhere, with the original material, I killed again. Go figure.

I will never forget that week in Vegas, but I have let other bad nights slide. A cliché in comedy is that you never take the audience reaction at a Friday night late show to heart because it is always bad. No one has ever understood the reason. When Steve Martin received a Kennedy Center Honor a few years ago, a reporter said to him, “You haven’t done stand-up in twenty-five years but you got a standing ovation tonight. Why don’t you do stand-up again?” Martin reportedly answered, “Second show, Friday night.”

For my writers who were interested in working on sitcoms, I brought to the meetings scripts from Good Times, The Jeffersons, and Barney Miller, the latter courtesy of Landesberg, who was starring as Detective Dietrich. I urged them to rewrite the scripts as an exercise, to see if they could improve on the scripts that were being filmed. I also wanted to get them used to not only the sitcom form but also what the writers’ room atmosphere was like on a series.

I must have done something right.

After Danny Arnold, the creative genius behind Ba

rney Miller, had a heart attack . . . or two or three—he had an oxygen tent on the set so he could continue to work—ABC insisted he bring in more writing help. Landesberg suggested they take a look at the spec script Frank ’n’ Stein had penned. By the following season Frank ’n’ Stein were story editors. They later won an Emmy for the show and also created Mr. Belvedere.

People criticize TV commercials, claim they make us do things we wouldn’t ordinarily do. It’s true. After seeing a couple of commercials the other night, I got so fed up I turned off the TV and read a book. (Frank Dungan, April 26, 1978)

Nadler met people from the Garry Marshall camp and almost immediately began writing for their smash hits Happy Days and Laverne & Shirley. He also wrote for Chico and the Man and Perfect Strangers (which originally was to costar Louie Anderson). Mister Geno would write most notably for Who’s the Boss? The team of Rod Ash and Mark Curtiss would write for Fridays, Shelley Duvall’s Faerie Tale Theater, and Sledge Hammer!

Everything is bad for you. I heard the government has just come up with another thing they say you shouldn’t put into your body . . . bullets. The healthiest thing you can do nowadays is die! (Ash & Curtiss, date unknown)

Wayne Kline wrote for Fernwood Tonight and Laugh-In before I got him on Good Times. He then worked at In Living Color. Most notably, he became a staff writer on talk shows—in the ’80s on Thicke of the Night with Alan Thicke and the Late Show with Joan Rivers, then for Leno’s Tonight Show from its debut in 1992 through 2009, when he moved over to the ill-fated Jay Leno Show. When Leno threw him overboard, he joined Letterman. Another writer, Larry Jacobson, would sometimes show up at my door at 11 o’clock at night with a page of jokes. He pushed and pushed and finally hit with Married . . . with Children before writing for Letterman and then switching to Leno.

The brilliant Paul Mooney wrote for Good Times and for me even as he was helping Richard Pryor craft his act in the mid-’70s. Years later he became the head writer for In Living Color, where he created Homey D. Clown, played by Damon Wayans. Steve Oedekirk also worked on In Living Color, where he connected with Jim Carrey and subsequently collaborated on the Ace Ventura films as well as Bruce Almighty. He also wrote The Nutty Professor for Eddie Murphy and Patch Adams for Robin Williams. Jack Handey wrote for Steve Martin and was responsible for “Deep Thoughts by Jack Handey” on Saturday Night Live. Allan Stephan would write and produce Roseanne. Alan Zweibel (Saturday Night Live) and the team of Jim Mulholland and Michael Barrie (the Tonight Show with Johnny Carson) probably still owe me some jokes!

Byron went from my writing staff to cohosting the TV series Real People for five years. He then went back to stand-up before creating his own syndicated late-night talk show, the Byron Allen Show. He sold that show station by station across the country. He would not give up. That series ran for another five years. Now he’s a TV mogul, producing and hosting several shows, including Comics Unleashed, on which comedians chat about their lives.

Jumping to the head of the class, however, was Letterman, who was given his morning show in 1980. His director was Hal Gurnee, the same director I auditioned for when I made my national TV debut with Jack Paar. Letterman thought his morning show was great, but after weeks of low ratings, the network blew that baby out. He was devastated. Sitting on my couch, he went on and on about how hard he had worked and how he didn’t know what he could do next.

“Don’t worry,” I said, “you’ll get another shot.” But the truth is that I thought he was done.

I felt the same thing about Steve Martin after I saw him open for singer Phoebe Snow at the Troubadour in LA around 1975. The crowd was filled with industry people—a tough audience. He wore a black suit, not a white one. He did his balloon animal bit. He played the banjo. He died a comic’s lonely death.

I went backstage and told him, “Hey man, you have to let this stand-up thing go. You have a nice job writing for that Dick Van Dyke show (which costarred Andy Kaufman). The people in these audiences are the ones who might hire you for other writing gigs. If they keep seeing you do this act, they will never hire you again.”

Steve said he had some gigs coming up with the Nitty Gritty Dirt Band and then he was going to New York to guest host a late-night show called NBC’s Saturday Night. “Then I’ll take a look and see what I should do,” he said. On that late-night show (which was later renamed Saturday Night Live) he sang “King Tut,” was one of the “two wild and crazy guys” with Dan Aykroyd, and became a sensation. That’s right, people, I told Steve Martin to get off the stage!

I was wrong about him, and I am glad I was wrong about Letterman too.

Since Good Times, some people come to a stand-up gig to see Jimmie Walker and some come to see J. J., that kid who popped into their living room and was part of their family once a week when they were growing up. People approach me and say, “How come you ain’t smilin’? Say ‘dyn-o-mite!’” or “I love the show you did about . . . ” But those who knew me prior to Good Times were surprised I was so loosey-goosey on the show. They knew me as fairly serious, someone who worked hard and was, basically, a loner. They knew that all I wanted to be was a stand-up comic, not a character on a sitcom.

I wanted people to see me as a comedian, not a cartoon character. Jerry Seinfeld overcame that difficulty perfectly by actually playing a stand-up comic on his TV series. The audience knew that was who he really was. For most of us, though, separating yourself from a successful character is problematic. Michael Richards, Kramer on Seinfeld, could not do it. Henry Winkler could not do it.

Leonard Nimoy tried to continue as a serious actor, but his fame as Spock on the cult TV sensation Star Trek overwhelmed him. Nearly a decade after he last played the Vulcan on television, he even wrote a book called I Am Not Spock.

I can relate.

I am not J. J. I just played him on TV.

What I did not know during the early days of Good Times was that J. J. would become a flashpoint for a controversy about race and that I would become the whipping boy.

7

The Whipping Boy

THE POWER THAT CAME WITH FAME DID GO TO MY HEAD—ONCE. Opening for Barry Manilow at the Circle Star Theatre in San Francisco at the height of his popularity, I was feeling pretty good about myself. I had come a long way and so had he—I knew Barry a little when he was the substitute piano player at the Improv in New York. When I arrived at the theater for a rehearsal, I saw a huge concert grand piano taking up the whole middle of the stage. This was a theater in the round. With the piano consuming so much space, I would have to work on the edges of the stage. I told the theater workers to move the piano to the side.

“Excuse us,” one of them said, “but it’s tuned and can’t be moved. Could you work around it?”

“Absolutely not!” Then I went on a rant in front of the entire crew about how great an act I was and that I deserved my place on stage and if they didn’t move that damn piano then I was going to walk!

Barry arrived and asked what was the problem. I told him in no uncertain terms. He was understanding but pointed out that if they moved the piano they would have to move it back to center stage after my performance, which would require tuning it again. There wasn’t enough time to do that between acts. I did not care—I wanted the piano moved! Finally, the general manager of the theater came to us. I bitched to him too.

He nodded his head. “You’re right, Mr. Walker.”

I was feeling righteous indeed.

“You’re right,” he continued. “You should walk. Thank you for coming. You are released from your contract.”

“But . . . ”

He turned and left.

Everyone in the theater fell silent, including me. I slinked out feeling about six inches tall.

I won’t sugarcoat what I did: I was wrong. As my mother would say, I showed out. The worst part was that I imagined everyone there thinking to themselves, “I used to like this guy.” I wrote Barry a letter of apology, and to this day I am embarrassed about that

incident. I never let anything like that ever happen again.

You are never as big a star as you think you are. Reality will knock you down a peg, sooner or later.

Sometimes when we meet, fans don’t realize that they are talking to a real human being and not a TV character. Because I was in their homes every week for years, when people see me in person, they talk to me like a family member, like I know them and they know me. But neither is true. It seems so strange to me when people get so personal when we first meet.

Years after Good Times I was working out at a gym and a guy who made Arnold Schwarzenegger look like Don Knotts came up and said, “Mr. Walker, you changed my life.”

I puffed up my chest a little, which took some effort.

“When I was a kid,” he said, “everybody laughed that I was as skinny and ugly as J. J. on Good Times.”

The air went out of me.

“I got so tired of that,” he went on, “that I started going to the gym, working out. I entered bodybuilding contests. And I won the state championship. I went back to those people and showed them my first-place trophy! After that, they never said I was as ugly as you!”

Nice to hear it. Thanks. I guess.

During the run of the series I was a recognizable figure from TV, but I was a recognizable black figure from TV. I was reminded of that while dating Stacey. She loved having her long, blond hair blow in the wind as we rode in my convertible Mercedes. One day driving down Sunset Boulevard a cop pulled us over. I expected him to come to the driver’s side and ask for my license. Instead, he went to the passenger side and asked Stacey, “Are you alright? We have a report of a woman being held against her will in a car on Sunset.”

Dynomite!: Good Times, Bad Times, Our Times--A Memoir

Dynomite!: Good Times, Bad Times, Our Times--A Memoir