- Home

- Jimmie Walker

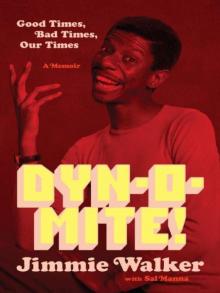

Dynomite!: Good Times, Bad Times, Our Times--A Memoir Page 14

Dynomite!: Good Times, Bad Times, Our Times--A Memoir Read online

Page 14

Yeah, right.

Stacey said, “No, I’m fine” and made a point of adding, “This is my boyfriend, Jimmie Walker.” The cop recognized me, gave me a dirty look, and walked away without another word.

When I was invited to be a contestant on the Tattletales game show, I needed to have a woman with me so we could be one of its celebrity couples. I brought Stacey. The producers’ faces flushed white—and I mean that in every way possible. They took me aside and said that, though they liked Stacey, they had affiliates in the South, and having her and me together would not be a good idea for the show.

“If you can bring a black girl,” they said, “give us a call and we’ll have you back.”

I asked Jere Fields, a black actress I barely knew, to come on the show with me. We had no relationship whatsoever, but she pretended to be my wife. According to information on the Internet, I have supposedly been married to Jere ever since! This is probably news to her: I have not seen her in more than thirty years. Maybe that is the perfect marriage!

We never went as far as showing a serious interracial relationship on Good Times, only an innocent one with young Michael—not as threatening as an adult one. But real life was often reflected in the series. That was no accident. Lear regularly called me and other cast members into the writers’ room to meet with them and the story editors to talk about our personal experiences as black men and women. Lear, in particular, wanted to absorb everything he could. Like my white friends at Yankee Stadium when I was a kid, he really wanted to know about us.

For me, these were almost like therapy sessions. A script about how black students were often promoted to higher grades without actually receiving the education necessary? Well, I could certainly talk about that. During the first couple seasons writers such as Roger Shulman and John Baskin, and Kim Weiskopf and Michael Baser for a couple of seasons after them, wanted to know not only what happened but also how I felt about what happened. They listened to what we said and tried to incorporate our thoughts into their scripts. They really cared—and it did not matter whether they were white or black.

Of course, there was not as much merriment in any ghetto, including my Melrose projects, as there was around the Evans household on Good Times. We were a sitcom, not a reality show. But there sure was a whole lot more reality than seen in any other TV series of any kind. I think there was more reality than most of today’s reality shows!

Good Times explored topics never before explored on television. Our second episode had aspiring artist J. J. paint a portrait of a black Jesus. That episode, about whether to enter the painting in an art contest, would be as controversial today as it was then. (Black artist Ernie Barnes created many of J. J.’s paintings shown during the series, which helped make him and his distinctive style famous.)

Another episode that first season touched on the touchy subject of George Washington being a slave owner. Another slipped in the fact that high blood pressure was the number-one killer of black males. And then there was the one in which J. J. was passed on to his senior year despite failing grades. In that episode the family questioned the validity of standardized testing. An exam asked students to fill in the blank for “cup and ______.” But instead of writing “cup and saucer,” the inner-city kid wrote “cup and table” because at his poor home they did not have saucers to put between a cup and the table. Other subjects included James being too old for a government job program and the evils of a corrupt evangelist. For story ideas the writers only had to read the front page of the newspaper.

J. J. was always the good kid who should have gone bad but never did. In a two-parter the next season he was accused of holding up a liquor store on his eighteenth birthday, presumably for money to buy art supplies. The entire family held a vigil at the police station while they tried to raise the bail money. Florida was on the verge of an emotional breakdown. James was desperate. They almost turned to a loan shark. Then the real robber was caught and innocent J. J. was released. But he had already lost his job because his employer found out about the arrest.

In another two-parter the Satan’s Knights recruited a reluctant J. J. into their gang. With J. J. on his way to a gang fight, James caught up with him to stop him. As the two tried to flee the fight, J. J. was shot. James wanted to hunt down the punk who shot his son, but Florida convinced him to let the system take its course after the boy was arrested. At the shooter’s trial James showed compassion for the boy and his broken family.

Another plot that second season depicted a senior citizen with money troubles who was forced to resort to eating dog food. Other subjects: upper-class blacks (“Oreos”), teen pregnancy, and the highly charged issue of bussing.

The shows were thoughtful, which other people were in charge of, but also funny, which was in my wheelhouse. Through all of this, J. J. took the pie. He was goofy and outgoing, confident and street smart; he was never going to go to college, and he was sometimes lazy. He was like a lot of teenagers in any family, black or white. That J. J. existed did not mean that all young black men were J. J. any more than because there was an Arthur Fonzarelli on Happy Days that all young Italian Americans were punks in leather jackets. And not so by the way: Both of them pretended to be more “street” than they really were. At heart J. J. was genuine and well meaning.

Then, just before the premiere of the third season, all hell broke loose. Esther said of J. J. in the September 1975 issue of Ebony: “He’s 18 and he doesn’t work. He can’t read and write. He doesn’t think. The show didn’t start out to be that. Michael’s role of a bright, thinking child has been subtly reduced. Little by little, with the help of the artist, I suppose, because they couldn’t do that to me—they have made him more stupid and enlarged the role.” Negative images, she continued, “have been quietly slipped in on us through the character of the oldest child. I resent the imagery that says to black kids that you can make it by standing on the corner and saying ‘Dyn-o-mite!’”

Talk about black-on-black crime! The media—both black and white—jumped on the controversy. The show that the public and critics had praised for two years was now being trashed by its top-billed and highly respected star. That was news, and the press took off with it.

I tried to stay out of the firestorm. I responded in the Ebony article with “I don’t think any TV show can put out an image to save people. My advice is do not follow me. I don’t want to be a follower or a leader . . . just a doer.” I deflected the subject as best I could when I told TV Guide that “I’m no actor. I’m a comic who lucked into a good thing. What the show has done for me, with all that exposure, is get me where I’m goin’ a lot quicker.” I told anyone who would listen that kids needed parental guidance and that sitting them in front of the TV with J. J. as the babysitter did not qualify.

I never criticized Esther or John. You will not find one negative word in print from me about either of them. I never had an argument or got upset with them in person either. It was not in my personality to wallow in my hurt feelings. It still isn’t. I’m a realist. Life is what it is. I accept what happens and then, hopefully, move forward. Bern Nadette, who was so close with Esther that they were like mother and daughter, would say, à la Rodney King, “Can’t we just get along?” But I never thought, “Oh gee, I wish we could be friends and hang out.” I did not think that was that important or necessary. I just kept trying to be the funniest I could be on the show—which was my job.

Carl Rowan, a renowned black columnist for the Washington Post, had it right: “‘Jr.’ is a hilarious composite of all those enchanting, exasperating creatures groping along that treacherous path between adolescence and adulthood. If ‘Jr.’ is a little exaggerated for the sake of belly laughs, well, so was Jim Nabors’ portrayal of ‘Gomer Pyle.’ That’s entertainment, baby!”

I could not imagine that any comments I made to the press really mattered in the long run anyway. At the time I was quoted as saying, “I don’t think anybody 20 years from now is going to remember what I said.”

I was a stand-up comic, and when this series was over, I would be on to the next case. So I stood there and took the hits. Lear would say in passing, “You’re a good guy for taking all this.”

I had no idea that the controversy would become part of television history or that decades later I would be signing memorabilia and t-shirts at Good Times events. I had no idea that the stigma would continue to today either. But the accusations of “cooning it up” fit the agenda of the politically correct and have been repeated over and over again. Although I sloughed it off in public, the fact is that Esther’s criticism, and also that of John and others—some of it very pointed and personal—seriously damaged my appeal in the black community. I still suffer today from the controversy that they sparked and stoked.

I was wrong about my viewpoint not mattering to posterity. Because this book is my story, it is time for me to finally speak up.

Here are a few facts: J. J. did not smoke, drink, or do drugs. The only thing he was hooked on was Kool-Aid. He was not a criminal, hustler, gangbanger, or shady character. Yes, he did not work much during those first two seasons. He was in high school! Even then, he still had a goal in life: He wanted to be a painter and he worked at his art, boasting that he was “the Van Gogh of the ghetto.” Yes, he used the word “jivin’,” but he was not illiterate or stupid. He was a nice kid who never hurt anyone and who dearly loved his family. And only one person succeeded by saying “dyn-o-mite!”—me, not J. J.

So what was the problem? Because we were a black family, there was enormous pressure for every Evans to be better and for every situation to be cause for progress. For some, such as Esther, that Thelma and Michael were college material was not enough; J. J. had to be too. For her, J. J. could not be “just” funny. In the inflammatory Ebony article, she admitted as much, saying that she was “more dedicated to doing a show of worth than to doing a funny show.”

Esther was right about one thing: The role of Michael was downsized as time went on. Feeding on the response of the viewers, the show’s writers increasingly put the spotlight on J. J. That was unfortunate for the show and for Ralph Carter. Esther stood up for his character, but because Ralph was a kid, he couldn’t do as much as the others to fight for stage time.

Making matters worse was that I was the outsider, the stand-up comic, the nonactor in a cast of veterans. During the first season the press was all about Esther and John. Beginning with the second season, however, I was the focus. All actors have egos, and theirs were bruised. At one point the producers stopped bringing all of my fan mail to the set so Esther and John wouldn’t get jealous of the thousands of pieces that would pour in every week to me, not them.

Neither of them ever confronted me face to face about their concerns. We never had a discussion about the situation. That was not surprising, because in all the time I was on the show Esther and John rarely ever said a word to me off the set about anything. It sounds crazy and impossible, but that is the truth. They talked to the other cast members, but not to me.

During rehearsals John would talk “about” me rather than to me. He just didn’t respect me and what I did as a comic. If I made a funny face, he would say to the director or the other actors, “Do we need to have actors mugging?” If I slipped in a joke in a sneak attack, he would say, “Do we really need that here?” I think he was trying to intimidate me, but I would not back off. He was the father figure on the set, but in reality I wasn’t that much younger than he was. J. J. was a teenager, seventeen years old when the show premiered, but Jimmie Walker was twenty-seven. John is only eight years older than me.

I have always admired John as an actor. He has put together a tremendous body of work, including what he did on Good Times. His later performances in Roots, Coming to America, and The West Wing were terrific. In 1975, while we were both in Good Times, we were also cast in the comedy Let’s Do It Again, starring Sidney Poitier and Bill Cosby. But, appropriately, we were never in a scene together.

This sequel to Uptown Saturday Night was about a pair of blue-collar workers who fix a boxing match by using hypnotism on an unlikely fighter to win a big bet. Given my skinny body type, I was on Poitier’s radar for the role of boxer Bootney Farnsworth.

Poitier, who also directed the film, came to the Store to see me perform and afterward wanted to speak to me. But he ran into Landesberg instead.

“Is J. J. here?” he asked in that very soft voice of his.

Landesberg said, “His name is Jimmie, but I think he left.”

“I’m doing a movie and I would like J. J. to come in to talk to us.”

Landesberg phoned me. “I don’t believe it, man, but Sidney Poitier was at the Store looking for J. J. and wants to put you in a movie.”

I went to the office of the man, the black icon, who had starred in such great films as In the Heat of the Night and Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner and was the first black to win the Best Actor Oscar, for Lilies of the Field.

“J. J., have you ever done movies?” he said.

“My name is Jimmie.” Then I told him about my Badge 373 experience.

“But no major part in a movie?”

“No, but I can do it.”

“You don’t even know what it is.”

“That’s okay. I can do anything.” You have to have confidence!

Poitier put a director’s optical viewfinder up to his eye and stared at me from every angle.

“J. J., let me see if you are mad.”

I gave him my “angry.”

“Oh, J. J., much too big. Take it down.”

So I gave him a “less angry.”

“Now let me see you happy.”

I flashed him a big smile.

“Oh, J. J., much too big. Take it down.”

I did.

“Oh no, less. The camera is not TV. This is cinema.”

I smiled again, but less enthusiastically.

“Okay, I will direct you and then I will take it down even further.”

I had only a few lines in the film. I spent most of my time boxing. But always Poitier would want my reaction “not so big. We don’t want you to jump out of the screen.” And he always called me J. J.

Poitier and Cosby would have made a good pairing for an Odd Couple . Poitier was so under control, so prepared, so soft spoken. Cosby, however, would hold court. He walked in talking about his comedy and about his life, and he never stopped. If Cosby is not talking, nobody is talking. One phrase you will never hear from Cosby is “So what do you think?”

Poitier and his crew would be almost ready for a shot and suddenly Cosby would say, “I got an idea. Hey Sid, why don’t we change that so I come in from over here, you put this hat on and these glasses, and then that happens over there?”

A very calm Poitier would answer, “Bill, I already have the scene mapped. We have lighting. We have camera ready. A change would cause many problems.”

“Come on, just try it once. Sid! Just once!”

“Alright. We will try it.”

They would take another half-hour and make the changes. Then we would do the scene, and nine times out of ten that was the version of the scene that made the film. Cosby does pontificate. He does come down from the Mount with the tablets. But he has usually been right.

The film received good reviews and is still well thought of today. The rapper Notorious B.I.G. even took his alias, Biggie Smalls, from one of the characters. In an era of cheesy blaxploitation flicks, Let’s Do It Again was a solid comedy.

I was busy on other projects too, from working with my own writing staff and performing at the Store to making my Las Vegas debut opening for Petula Clark at the Riviera and starring in a TV movie.

The Greatest Thing That Almost Happened was about a high school basketball player who learns he has leukemia before the state championship tournament. It was my first, and as it turned out, the only major dramatic role of my career. Talk about being fearless and plowing ahead. The man playing my father was James Earl Jones, probably be

st known at the time for The Great White Hope, for which he was nominated for an Oscar.

Landesberg commiserated with me about my insecurity about being able to hang in there with such an accomplished actor. “Did you know that when Laurence Olivier was going to do Hamlet, he felt he was not worthy?” he said dead serious. “I mean, how could he perform that role when the great Gabby Hayes had done it before? That’s right. Gabby Hayes was once a great English actor before he left the theater to become Hopalong Cassidy’s sidekick.”

Steve created the whole bit on the spot. He was terrific with dialects and impressions, and he had Olivier in his refined English accent asking crusty cowboy Gabby, “Why do you want to leave the London theater and go to the United States? You are the best Hamlet ever!”

“I got to be seen!” replied Gabby in his Western drawl. “I got to be seen!”

“But my good man, you are going to play a cowboy.”

“If I can play Hamlet,” answered Gabby, “I can play Buckshot!”

Steve’s bit helped me be a little less nervous when I went in for our first rehearsal.

But when James Earl Jones read his lines, he was completely monotone. No emotion at all. Boring. I was surprised. I thought this guy was supposed to be a great actor. A few rehearsals later he was doing the same thing. I told friends, “What’s the big deal about this James Earl Jones?” What a letdown, I thought to myself.

So I was feeling confident about a scene with him on the first day of shooting. Until he opened his mouth. He was excited, completely into the scene, and he nailed it. He was James Earl Jones. I was stunned, wondering where all of this energy came from. Not being an actor, I did not know that he—and many actors—rehearsed at a lower energy level. Once we were actually shooting, he was amazing!

Dynomite!: Good Times, Bad Times, Our Times--A Memoir

Dynomite!: Good Times, Bad Times, Our Times--A Memoir