- Home

- Jimmie Walker

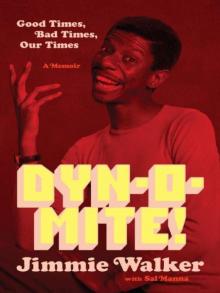

Dynomite!: Good Times, Bad Times, Our Times--A Memoir Page 15

Dynomite!: Good Times, Bad Times, Our Times--A Memoir Read online

Page 15

The Greatest Thing That Almost Happened—and even my performance—received very good reviews. I hear James Earl Jones continued with his career too.

I was also finally invited on to the Tonight Show, but Carson was not behind the desk. The guest host was none other than David Brenner, just like he said he would be years earlier. I saw him in the hallway of the studio and he said, “Hey, tonight we’re going to do that cab story. See you out there.” He broke out the cab joke he had concocted so long ago. I couldn’t believe he even remembered it.

To the credit of everyone on Good Times, despite the jibes in the press, we were always professional at work. A reporter for TV Guide wrote that during our second season, at the end of the scene in the Satan’s Knights episode in which J. J. was shot and laid on the sidewalk unconscious, James yelled, “Somebody call an ambulance!”

The director yelled, “Cut!”

Amos looked down at me and added, with feeling, “This’ll kill us in the Nielsens if he dies!”

But our cast did not have a familial relationship. Amos later told reporters that “although we played a family on the show, the cast was not really like a family. We would punch in and punch out like any other job.”

Norman would occasionally host dinner parties, but the entire cast never attended any of them. The Evans Family was a family of orphans. Looking back I think if we had the cast chemistry of a show like The Jeffersons , we could have run for a dozen years or more instead of the six that we did.

Of the original cast I got along very well with Ralph, though he was in school for much of the day. He was a cool kid. Bern Nadette was my only close friend, truly closer to me than my own sister. She helped me pick out gifts for girlfriends and hung out with me and my comedy buddies at Canter’s and Theodore’s. She went to the Comedy Store with us too.

“All you guys talk about is comedy! Comedy and jokes!” she rightly complained.

She was stunned at how visceral the conversations would be. George Miller would just rip people. “He doesn’t have any jokes,” he would say of another comic in that slow drawl of his. “That’s not funny.” Anything George said was funny, even the most biting cuts you ever heard. He said of comedy duos: “I love to see double acts break up. Then I can see them fail individually.” A typical joke of his:

I read this article that said your car reflects your personality. I don’t have a car.

Bern Nadette tried to get into how comedians are with each other and came to a couple of writers’ meetings. Finally, though, after I headed to the Store as usual to try the jokes out on stage, she said, “Stop! No more jokes!”

The attack piece in Ebony may have personally offended Lear more than me, because the article also slammed the show for not having enough black writers. No one outside of Norman Lear had done more to further the cause of blacks in the television industry, including behind the camera. Now, suddenly, according to some critics, Lear was running a plantation. After working so hard to make Good Times and other black shows happen, the backstabbing broke his heart. Beginning the day he came to the set with that article in hand, he never felt the same toward Good Times.

Beginning with that article I have rarely read anything about myself in print. Reading reviews is like an out-of-body experience, as if they are writing about another person. It is said that people believe 90 percent of what they read in a newspaper, but disagree with 90 percent of the 10 percent they think they know something about.

If someone writes something good in a review, they never get it exactly right, so it is not very useful. If it’s a bad review, you get upset, which does you no good either. Besides, there is really no reason to read a bad review—because you can count on someone coming up to you and telling you all about it anyway!

“Did you see that review about you? Called you an Uncle Tom! Said you were, and I think the quote was, ‘one of the worst things to ever happen to black people in the last thirty years.’ I don’t agree with that at all. Did you see that?”

“No, but I guess I don’t have to now.”

I suppose that is why I have never actually seen an episode of Good Times. I was there. I know what we did and what the show looked like. People told me all about every one of them—and still do. I know people enjoyed them—and still do—but I never had a reason to watch an episode.

Heading into our third season Amos and Rolle threatened to quit, so they were offered more money to stay. Esther quickly took it, but John hesitated. As he did, the writers came up with storylines about his character’s possible departure. That’s why John does not appear in two episodes of the third season. In one of them, Lou Gossett Jr. arrived as Florida’s brother Wilbert. If John bolted, Uncle Wilbert was in the wings to take over as the man in the Evans household. John agreed to return at the last minute.

For season three I was bumped up in the billing hierarchy with a new credit: “and Jimmie Walker as J. J.” on a single card. High school graduate J. J. now had a steady job (at first delivering chicken for the Chicken Shack and then for a rib joint) while attending art school at night. The storylines were as topical and incendiary as ever, including handguns in the home, slimy but smooth politicians, the high cost of medical care, adoption for an unwed mother, the disabled in society (a deaf friend), the numbers racket, lonely senior citizens, and community protests. Those were not even the most controversial.

In one episode J. J. and his girlfriend (played by Debbie Allen) decided to get married despite the objections of both sets of parents. They claimed to go to the prom but instead eloped. When she begins to get sick, J. J. discovers she is a heroin addict. When she loses her drugs, she runs away in search of another score.

In another the FBI came to the projects looking for Florida’s nephew in connection with a bank robbery involving the Black Falcons. (Presumably, saying Black Panthers would have been too obvious.) Michael was incensed that the FBI was spending its time on a robbery when there were murder cases involving black civil rights leaders still unsolved. He confronted the FBI agents with “Who shot Medgar Evers?” recalling the activist killed in Mississippi in 1963. Michael and the FBI tangled in another episode after he had a pamphlet about dictator Fidel Castro mailed to the Evans home directly from Cuba.

But the episode that season that has endured the most strongly in pop culture is the one in which J. J. thought he had contracted a venereal disease.

THELMA

You got VD?

J. J.

You don’t have to broadcast it on the Six O’clock News!

Ironically, that was among the first times VD was ever mentioned on national television.

J. J. worried that he may have given it to his girlfriend too. He scrambled to get himself cured before his parents found out. In the scene at the health clinic a young comic with a prominent chin and curly hair beneath his wool hat spoke his first lines on national television—Jay Leno. I had been pushing Lear to get Leno on the show for months. Every day I said to him, “How about Jay?” I became so annoying that when I passed him in a hallway, before I could open my mouth, he would say, “Yes, I know, I’ve got it, Jay Leno!”

Leno’s character asked, “What are you here for?”

“I got a cold,” lied an embarrassed J. J.

“Cold? That’s funny,” Leno replied, “everyone else is here for VD.”

By any measure season three was as groundbreaking and positive in terms of the image and perception of blacks as the show’s first two seasons. The public may not have realized it—and it may come as a shock to media critics today—but the writers and producers decided to cool it with the catchphrase too. For nine of the last ten episodes, J. J. never said “dyn-o-mite.” And I didn’t have a problem with that at all.

Our ratings did slip. We were the twenty-fourth highest-rated show of the year, with just under fifteen million households watching each week. But that had more to do with the competition than with what we were doing. We had beaten Happy Days head to head the previous season.

Now Richie and Fonzie had built some momentum and were beating us.

By this point Amos was not happy about anything. Finally, Lear had enough of his complaining. Prior to taping the 1976–77 season—our fourth—he was fired: “I was informed by phone that I was considered a disruptive factor and that my option would not be picked up for that season or any other episodes,” John recalled.

Such firings in Hollywood are rarely so public and blunt. When Mike Evans, who cocreated Good Times, left his role as Lionel on The Jeffersons after its first season, the story fed to the public was that he wanted to concentrate on his Good Times writing responsibilities. In truth, he didn’t have any. What actually happened was that Evans demanded more money.

The first several episodes of The Jeffersons had been filmed; they would begin airing as a midseason replacement in January. We were all gathered at the Tandem Productions Christmas party in 1974, when Evans went up to Lear and asked for a raise or else a release from his contract. Lear turned to one of his executives, Alan Horn, and asked, “Would there be any problem with that?”

“No,” said Horn.

“Okay,” said Lear, “you’re released.”

That was not the answer Evans expected. Not only was he immediately replaced, but he was replaced by an actor with his same last name—Damon Evans. Mike would not be seen on The Jeffersons again for four years. Ouch.

When Amos was axed, he lashed out and did not mind getting personal. “The writers would prefer to put a chicken hat on J. J. and have him prance around saying ‘DY-NO-MITE,’” he screamed to the press. “And that way they could waste a few minutes and not have to write meaningful dialogue.” He charged that “the studio wants to boost ‘Good Times’ mediocre ratings by making Jimmie Walker—who plays my son J. J.—head of the family. What they are after is a powerful character to combat ‘The Fonz.’ And I’m not the one who can compete with that age group. . . . The character of J. J. will have to mature very quickly if he is going to become the family boss. Maybe he can pull it off. We’ll see.”

If the decision had been up to me, I would have preferred that John stay and the show remain more of an ensemble. Norton needed Kramden, Fonzie needed Richie, and J. J. needed James Senior. Nobody wanted me up front all the time, including me. Garry Marshall, the genius behind Happy Days, managed to get Ron Howard to take a backseat every now and then to Henry Winkler. But Amos was not willing to do the same with me.

Season four’s opening episode began with my announcing myself as “Kid Dyn-o-mite!” My credit card now read, “And also starring Jimmie Walker as J. J.” For the first time I was officially “starring.”

In the storyline of the season’s first show James had partnered in an auto mechanic’s garage in his native Mississippi, where the Evans family planned to move into a new home. The episode ended with the news that he had been killed in an auto accident. Fans still recall the horrible revelation and Florida’s reaction on the following episode: “Damn, damn, DAMN!” That was in a day when saying “damn” was not permissible on television. But this occasion warranted the expletive. That moment was one of the most memorable as well as one of the finest in Esther’s laudable career.

With the family fatherless, J. J. became the man of the house. The show continued to tackle difficult subjects, including gangs, drugs, crime, politics, and even atheism, thanks to the introduction of a romantic interest for Florida who objected to “under God” in the Pledge of Allegiance. The Carl Dixon character, played by Moses Gunn, also brought up the subject of cancer when doctors found a spot on his lung.

In one episode that season a corrupt city alderman coerced J. J. into giving a speech on his behalf by threatening to cause the eviction of his family. J. J. took the mike but then mocked the politician. In another show, when J. J. lost his job, he became a numbers runner—the only time he did anything significantly illegal in the course of the series. After he bought expensive gifts for everybody, Florida uncovered the source of his funds. She demanded he quit and, when J. J. refused, she threw him out of the apartment. J. J. moved in with the hustlers and unhappily discovered they were also pimps and drug dealers. When the police raided the place, J. J. narrowly escaped arrest. In another episode a friend of J. J.’s lost his shot at becoming a sports star and became depressed. He locked himself in J. J.’s bathroom and overdosed on pills in a suicide attempt. J. J. saved his life.

This was all in a sitcom! There were episodes that were standard fare, the typical domestic situations that situation comedies always have had. But Good Times went as far out on the limb as any sitcom, even those from Lear.

As time went on, the scripts increasingly included aspects of the current lives of the actors, which is typical of TV series that are successful. For example, in season four, J. J. became a talent manager. He discovered first a female singer and, in another episode, a stand-up comic. For the latter he borrowed money from a loan shark to buy a gig at a nightclub. When the comic caught stage fright and bailed, J. J. could not pay back the loan. Thugs were ready to take their pound of his flesh. In the end the club owner paid the loan shark in return for J. J. mopping floors for a month. The name used for the management company on the show was Ebony Genius, which was what I laughingly called myself in my act and, not coincidentally, was the name of the management company I had in real life.

Running Ebony Genius was my lawyer, Jerry Kushnick, and a pit bull named Helen Gorman. During my first year on Good Times my ICM agent hardly paid any attention to me. One day his assistant, Helen, realized that I was a client. She told her boss: “There’s a guy allegedly with us and you have never visited him on the set!”

He replied, “Hey, we’re getting our commissions. So what?”

She asked if anyone was going to “cover” me—in other words, keep track of what I was doing and try to advance my career. Her boss, who barely knew what I did, said he was busy. Helen offered, “I’ll cover him,” which was very ambitious for someone merely an assistant. After talking to people who thought I was funny, thought I might have a future in show business, she even came to meet me on the set. She was the one who fought for my “starring” credit on the series, something I really didn’t want or care about but that meant something in the business.

Meanwhile I had told Jerry about my idea for a management company that specialized in the comedy business, both writers and stand-ups. My theory was that if we could corral the best comedy talent—especially writers—we could become players in television. Naturally, I was thinking about the very talented guys on my staff who could use some management help. I asked Helen if she wanted to work with Jerry on that idea, and she jumped on it. She left ICM, Jerry moved to LA, and around 1975 we formed Ebony Genius Management, with me as president.

I believe I was the only black manager in Hollywood other than those who worked with music acts. The only other possibility would have been Monte Kay, who handled Flip Wilson. In his early years Kay supposedly was not averse to letting black artists think he was a fair-skinned black instead of what he really was—a white guy with a really deep tan.

Among our first clients were Letterman, Leno, Boosler, Frank ’n’ Stein, Shirley Hemphill, and April Kelly. I suggested many others who I thought were talented. Helen’s first question would always be “What’s he going to do for us?” I would answer, “I don’t know. But he’s funny!”

Helen didn’t think Dave or Jay were funny. To her Letterman was a dark, brooding figure. She could hardly understand why he was even trying to do comedy. As for Leno, to her Jay was a crazy guy who wore a stupid hat, a motorcycle jacket, a blue-jean shirt, and a big belt buckle. She especially despised when he would drive up to a Hollywood meeting on one of his big motorcycles. She would be nice to his face, but when he turned his back, the best she could say was “We’ll keep him on the road and he’ll be happy.”

Whenever she wanted to drop Leno or Letterman, I wouldn’t let her. When she felt trying to promote them was costing us too much money, she refused to pa

y the office expenses for making copies of their photos, résumés, and tapes as well as the postage for sending them to club owners, producers, and so on. I stepped in and paid for them out of my own pocket for two years. I did not want to give her any excuse to cut them loose—and I never told either of them.

I spent a lot of time and effort to get Leno work, and not just on Good Times. Merv Griffin liked having me on his show, so I told Paul Abeyta, his talent coordinator, that I would go on but only if for every time I was on, he would also give Leno a shot. And that’s what he did. Sometimes Abeyta would call and say, “Yes, I know, a shot for Leno, but we need you for the show on Tuesday.”

We started cooking, baby! Jay was on the road doing gigs nearly every week of the year; Frank ’n’ Stein landed Barney Miller; April hit with Mork & Mindy.

No one came further than Shirley Hemphill. She arrived in LA from North Carolina with nothing. She was one of the rare black female stand-up comics. Nearly every night she showed up at the Store hoping to get on stage. We did not know that she was living in a single room on Skid Row in downtown Los Angeles and would walk the miles and miles to the Sunset Strip. When we found out, Johnny Witherspoon or I began to drive her home at night. I brought her to Ebony Genius and got her work on the road, an acting spot on Good Times, and finally the role of Shirley, the wisecracking waitress, on What’s Happening!! Her proudest moment was when she was able to buy her own home.

In early 1977 Helen placed Letterman on The Jacksons variety show, where he received his first national exposure as a performer, and then on the Starland Vocal Band Show variety series that summer. We even produced a variety-show pilot called Rising Star that featured me, Letterman, Leno, his girlfriend, Adele, and a comedy troupe called the Village Idiots.

Boosler was getting some heat too. We had first met in New York at the Improv. Between comedy acts she would sing in a duo with Shelley Ackerman. But when they hung out with us comics at the Camelot, they were both very funny and could hold their own. I told them they could be a comedy team. They insisted they were singers.

Dynomite!: Good Times, Bad Times, Our Times--A Memoir

Dynomite!: Good Times, Bad Times, Our Times--A Memoir