- Home

- Jimmie Walker

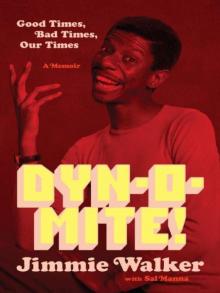

Dynomite!: Good Times, Bad Times, Our Times--A Memoir Page 5

Dynomite!: Good Times, Bad Times, Our Times--A Memoir Read online

Page 5

I met most of the leaders of the movement, including those with the Black Panthers. But the Panthers were formed and strongest in California. They were from Oakland and did not translate to New York and the East Coast quite as successfully. Stokely Carmichael, however, was one of us, a New Yorker. He moved from SNCC (Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee) to the Panther Party and was responsible for popularizing the term Black Power. Stokely was very smart. I was impressed that he had gone to the Bronx High School of Science, where you had to pass a test to get in. Some of us rarely passed a test when we were in high school.

Stokely started out believing in integration, but by the time we crossed paths he was into his “Back to Africa” phase.

“You know, Stokely,” I told him with a straight face. “There are a lot of white people who would love to see this ‘Back to Africa’ thing happen.”

He did not find that amusing. He got pissed and said, “Walker, maybe you are not relevant to the revolution.” He was probably right.

Stokely was a very serious guy, taking everything so hard. Life to him was black and white—and everything white was evil. He was the kind of radical who objected to using white toothpaste. But he was one Panther who said what he meant and meant what he said. In 1969 he did go back to Africa.

The Panthers earned a lot of good will in the black community because of their free-breakfast program for kids. Though launched in Oakland, the program soon had kitchens operating in cities across the country, feeding more than ten thousand children every day before they went to school. The Panthers helped instill self-worth in the black community too. They talked about standing up for ourselves, that sometimes we can’t turn the other cheek. They talked about not looking for a handout; sometimes we need to do things for ourselves. I could not disagree with that. Power to the people!

The rallies I performed at were very militant affairs, with the Panthers blaming all of the problems of the black man on white society. After one rally in the rain, when I used my Superman joke, I heard one Panther say, “The white man made it rain!”

Another common saying was “The telephone is for white people. A black person uses the drum!” When someone yelled during a rally, “Down with the white devil!” the Panthers’ white lawyer, William Kunstler, would stand up and scream, “Right on!”

My act was definitely antiwhite as well, though I have—excuse the expression—“blacked out” most of those particular jokes from my memory.

I love to see white folks who don’t work. Make me feel so good on the inside. “Why don’t you go get a job? Pull yourself up by your bootstraps! I’m tired of paying taxes for people like you!”

But all I wanted was stage time. So did everybody else. When Stokely would get going, he’d speak for an hour and a half. He was a star, as was the incendiary Rap Brown. The women were strong too. In truth, I thought Kathleen Cleaver was sharper than her husband Eldridge. And when Angela Davis was there, she would close the show. She was young, pretty, flamboyant, and a Communist. Whites had Jane Fonda; blacks had Angela Davis. They would wait hours on a hot day in the park to see and hear her finally. But they would first have to see and hear me:

The brothers tell me that our women, our black women, should always be ready to have sex with us so they can populate the world and there will be lots of us when the revolution come. The other day I get into a fight with my girlfriend. She tells me, “Jimmie, when it comes to you, I think I’m gonna take time off from the revolution.”

There were some in the movement I had my doubts about—opportunists who believed a little of what came out of their mouths but also knew what to parrot in order to get through. They hopped on the Black Power train for the chicks and the cash, and make no mistake about it—there was a lot of both. Not for me, of course. I was just the comic.

In the summer of 1968 the Panthers invited me to entertain at a series of seminars and workshops in Chicago. I was given the title Official Comedian for the Black Panthers in the East. I didn’t know if anybody else had a title, but I had one. Much of the leadership was there: Bobby Rush, Elaine Brown, David Hilliard, Fred Hampton, and the Cleavers among them. They were getting ready for the Democratic Convention. And all the talk was about how “The Man” was after us, about conspiracies and spies. I didn’t think I was that significant or important for J. Edgar Hoover to care about. But I was there, and I’m probably still in an FBI file today.

One night after a rally a group of us went to Fred Hampton’s apartment in Chicago. We knocked on the door and waited a couple of minutes. A woman cracked it open as if we might be burglars. She recognized a few of the others and let us in. The place was barren—a few chairs and a couple of lamps without shades turned on. Incense was burning.

Hampton was young, just twenty years old, but he had a commanding presence. When he brought together a number of militant groups, including the Black Panthers, Brown Berets, and Red Guard Party, he coined the term “rainbow coalition” long before Jesse Jackson borrowed it.

I sat with a couple of folks in his kitchen while he and others went into the living room. After more than an hour they rejoined us. Fred said matter of factly, with no fear or panic in his voice, “I don’t know how much longer I’m going to be around. I think they’re going to kill me.” “They” was the FBI, CIA—the US government. I was shocked. Why would they want to kill this guy? As we got up to leave, Fred hugged everybody, including me. It was a goodbye hug. I thought he was crazy about being targeted for death, that he needed to take a chill pill.

Later that summer, along with the rest of America, I watched the riots at the Democratic Convention on television. I would see certain Panthers get arrested and I would think, “Wow, I know that guy!”

A year later I was back in Chicago, opening at a club or theater, and I turned on the TV for the news. They said a Black Panther leader had been killed—it was Fred Hampton. They reported that the Chicago police had gone to Fred’s apartment and been attacked. The police then shot him dead. When I returned to New York and went to the East Wind, the story was different. They said Fred and his pregnant girlfriend were sleeping as the cops busted in. They shot him more than fifty times.

The truth was hard to find. Race colored everything. But Hampton turned out to have good reason to be paranoid. Uncovered later was the fact that the FBI was keeping tabs on him and the others, tapping their phones and infiltrating the group. I did not know it at the time, but William O’Neal, Hampton’s bodyguard and the head of security for the Chicago chapter of the Panthers, was actually working for the FBI.

I, however, was not a militant. Nor was I a “Negro,” which was a putdown. A Negro was someone like Aunt Inez. Her older generation, though they had experienced abuse from whites and talked about it all the time in private, would personally apologize to white people about the Freedom Riders and those in civil rights marches. When I was in Birmingham, Aunt Inez would tell white people, “I’m sorry. I don’t know about these young people today. They have nothing to do with us.”

Call me a Negitant. I was where most blacks were, like most people usually are—in the middle. I was just not that angry. Why would I be? I had not been around many white people to start with and had truly never witnessed whites treating us badly because of the color of our skin. The black people I was around didn’t spend our time wondering what the white people were doing to us. I didn’t believe white people were out to get us; I figured they had other, more important things to do. In fact, the whites I had come into contact with—my friends from the ballpark and teachers at SEEK—had actually helped me.

I heard what the Panthers and the Poets said, and I took it all in. But what they were yelling about was not part of my reality. As Godfrey Cambridge joked,

You people aren’t going back to Europe, and we aren’t going back to Africa. We got too much going here.

I believed in Satchel Paige’s line: “Don’t look back—somebody might be gaining on you.” I wasn’t looking back.

&nb

sp; The Last Poets finally got me to the Apollo. Frank Schiffman, the owner, and his son Bobby didn’t want them to perform there because they felt the Poets were too antiwhite and the crowd might get out of control. Even Honi Coles, the famed black tap dancer who had become production manager at the Apollo, objected. But the local community put on the pressure, and the Last Poets were booked—and so was I as their opening act.

My mother had first taken me to the Apollo when I was a child. I remember seeing Frankie Lymon and the Teenagers, the Harlem singing group who had the massive hit “Why Do Fools Fall in Love,” and later Sam Cooke and then James Brown when he truly was Mr. Dynamite. For someone in the ghetto, going to the Apollo was like a Jew going to Jerusalem or a Muslim going to Mecca. I never dreamed that someday I would be on that legendary stage. Although my mother had been upset with me about my career path ever since I quit the post office, she got over that disappointment in her son on the night I played the Apollo.

Well past midnight, long after the show was over, I hung around after everyone else had left. I walked on stage, still wearing the khaki safari jacket that was becoming my trademark. The one small lamp traditionally kept lit was the only illumination. I stood at center stage and thought about where I had come from and where I was now. Pure joy washed over me. I reveled in my moment, and, well, the moment was cool.

Soon I would get used to being on that stage—not as an opening act but as an emcee. I became one of two regular emcees, along with the unrelated and bald Roger Walker. But I wanted to do more than introduce acts. So I’d do my jokes too. Some artistes did not appreciate that.

The first night I worked as emcee was for a show with Wilson Pickett and Joe Simon. I did my bit, got my laughs, and then introduced Pickett with as much flair as I could muster.

“Now, ladies and gentlemen, you know him, you love him—welcome Wilson Pickett!”

Pickett, who was hugely popular, did his show, including hits like “In the Midnight Hour” and “Mustang Sally.” Immediately after he exited to his dressing room, the stage manager found me and said, “Mr. Pickett wants to see you in his dressing room.”

I thought, “Great, he probably liked some of my comedy and wants to compliment me.” First I returned to the stage for some more jokes and to introduce Joe Simon: “Ladies and gentlemen, you know him, you love him—welcome Joe Simon!”

Then I went to Pickett’s dressing room.

“I thought you were the emcee,” he said coldly.

“Yeah,” I said, “but I’m a comic too.”

“You emcee, right?”

“Well, yeah.”

“You’re the guy who brought me on?”

“Yeah.”

“What the fuck was that?!”

“What?”

“‘Ladies and gentlemen, Wilson Pickett’?”

“That’s it, right?”

“No, that’s not it. I’m the Wicked Mr. Pickett, and you say it at least three times, and you tell them all my hits. Forget the jokes. Then ‘Ladies and gentlemen, the Wicked Mr. Pickett!’ Then you get the fuck off.”

I walked out somewhat shaken, and the stage manager pointed me to Joe Simon’s dressing room.

“What was that?!” Simon yelled. “‘Ladies and gentlemen, Joe Simon’? Forget the jokes. This is what you say: ‘All the way from Louisiana, the man who gave us ‘Let’s Do It Over,’ ‘Teenager’s Prayer,’ ‘(You Keep Me) Hangin’ On,’ and his million-selling smash hit, ‘The Chokin’ Kind.’ Then you walk to one side of the stage and say, ‘Joe Simon!’ Then you walk to the other side of the stage and say, ‘Joe Simon!’ Then you walk to the center of the stage and say, ‘Joe Simon! He’s back there! He can’t hear you! Joe Simon!’ Then I come out.”

“I’ll be happy to do that intro, Mr. Simon,” I said. “But after I do my jokes.”

I stood up for my stand-up. Once, when I heard the Delfonics tuning up their voices behind the curtain while I had a couple of minutes left as an opening act, I yelled on stage for them to shut the hell up! But my attitude did not sit well with Honi Coles. He and other Apollo folks wanted me fired. But Bobby Schiffman liked me, so I stayed. I kept doing my jokes, every show, five shows a day, a couple days a week. I would close my time on stage with a joke about an algebra question my teacher supposedly asked me in school:

If Farmer Brown took five hours to plow his field, how many hours would it take Farmer Brown if he had Cousin George do half the field in one-third the time it took Farmer Brown, and if one of Farmer Brown’s horses was ill, slowing Farmer Brown down by 18 percent? Now, showing all work on a separate piece of paper, how long would it take Farmer Brown to plow his field? Give the answer in FEET!

I always managed to get the audiences laughing. That was not easy. Apollo crowds were notorious for being tough on performers who showed any weakness. One comic, Danny Rogers, got into it with a heckler, and the guy pulled out a gun and shot him.

So I went into Bobby’s office one day and asked for a raise from $400 a week. Honi was there. They looked at me like I was a Klansman at an NAACP convention.

“You’re lucky to be on that stage!” said Honi. Ever since the Last Poets, who he did not like, he had tagged me as an arrogant punk who did not know his place.

“I think I’m doing a good job.”

“Are you insane?” said Bobby. “You’re not an act. You’re an emcee. You don’t make the people happy. The acts make the people happy.”

Honi piled on: “You’re making a lot of trouble around here for a guy who ain’t shit and ain’t funny. Who the fuck do you think you are?”

“I’m Jimmie Walker!” I said, thinking that should be answer enough.

“Who the fuck is that?” said Honi.

Bobby waved his hand at me. “Get out of here!”

So I went to Frank, Bobby’s father.

“You really think you deserve a raise being an emcee at twenty years old?”

“I’m doing comedy too. That counts for something, doesn’t it?”

“Let me talk to Bobby.”

They gave me a $25-a-week raise.

My mom was probably never prouder of me than when she saw me at the Apollo. I heard that she would stand in the lobby and somehow subtly announce to the people walking in that her son was the emcee. I did consider myself lucky to be there, and I took advantage of it too. Every now and then I would spot a girl in the audience I knew from junior high, a girl who never noticed me back then, and I would get to impress her with a tour backstage and an inflated rap about how I knew Gladys Knight and the Pips, the Dells, Harold Melvin and the Blue Notes, the Emotions, Jerry “Ice Man” Butler, and on and on.

I became so familiar to the music acts that I was often booked for their shows on the rest of the “chitlin’ circuit.” Along with the Apollo, these were predominantly black theaters, such as the Uptown in Detroit, Regal in Chicago, Uptown in Philadelphia, and Fox in Detroit as well as clubs deep in the inner cities of America throughout the East, South, and Midwest. The unofficial circuit developed because at white theaters black acts were rarely allowed to perform and black audiences were hardly welcomed either.

One day at the Uptown in Detroit, a man and a woman came backstage and said they liked what I was doing. They asked if I would be interested in emceeing a tour around the country. They were from Motown Records, which was about to send out the Motortown Revue (aka Motown Revue). I met them again the next day at the Motown offices, where they told me more about the “truck and bus” tour—which meant everything we would need would be coming with us either by truck or bus.

Coincidentally, the first Motown act I had already worked with was Motown’s first act ever. In 1959 Marv Johnson recorded “Come to Me” for Tamla, Berry Gordy’s predecessor to Motown. Marv had several major hits over the next couple of years, such as “You Got What It Takes,” and he was Gordy’s first star. But when I opened his show at Detroit’s legendary 20 Grand nightclub, he was near the end of his Motown career.

The 20 G

rand, my first genuine club gig outside of the New York area, was a club where Gordy would go to see potential artists he could sign for his fledgling record company. Gordy sat in a booth along with an associate or two as well as his sister Anna, who would later marry Marvin Gaye. The artists worked their asses off trying to impress him.

Everyone from Smokey Robinson and the Miracles to the Supremes to Stevie Wonder had played there. A hard-core joint filled with sleazy lowlifes in the middle of the ghetto, the 20 Grand packed more guns than any place I have ever been. It made the Club Baron look like a convent. Everybody packed a piece, brother. How do I know? Because they were out in the open! They showed them, Chuck Berry style! (As a teenager, Berry famously flashed a handgun to steal a car.)

Everybody had a gun because fights were constantly threatening to break out. Every night I was at the 20 Grand there was a gun incident. The antihandgun folks won’t like to hear this, but gun proliferation actually stopped greater violence. If there was a fight brewing and someone pulled a gun, usually people said to themselves, “Well, maybe I will reconsider whether this fight is really worth continuing.” Fights did not start with guns, but showing a gun usually ended them.

Even the artists, such as Marv, would carry guns, sometimes to threaten whoever was supposed to pay them.

“Hey, where’s my money?” the musician would say.

If the club owner hesitated, the musician would show his piece. “I want my fuckin’ money!”

On occasion a friend of the owner would see what was happening, come up behind the musician, and pull their own gun. That was just business as usual.

After I exited the stage renowned Motown choreographer Cholly Atkins—who gained fame in a tap dance act with Honi Coles before he taught those great dance steps to the Temptations and all of Motown’s artists—loved to bust my chops: “Hey man, I heard those jokes you were doing. You’d better keep moving because I don’t have choreography fast enough for you to dodge a bullet!” Cholly taught me that you should work hard in show business, but don’t take the business so seriously that you don’t have all the fun you can along the way.

Dynomite!: Good Times, Bad Times, Our Times--A Memoir

Dynomite!: Good Times, Bad Times, Our Times--A Memoir