- Home

- Jimmie Walker

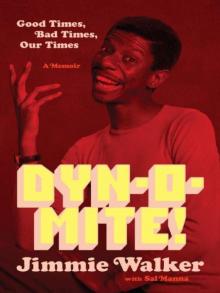

Dynomite!: Good Times, Bad Times, Our Times--A Memoir Page 6

Dynomite!: Good Times, Bad Times, Our Times--A Memoir Read online

Page 6

Playing the Regal in Chicago was just as dangerous as the 20 Grand. I never felt safe there. We came in on a Monday and played through Sunday. Everyone in that rough ghetto knew what day we would be paid—and most acts, especially black ones—were always paid in cash. We worked hard for that money: shows at noon, three, six, nine, and midnight on weekdays, and then another 2 a.m. show on weekends. We had to be careful walking to and from the theater, though the theater itself wasn’t secure either. Wardrobe would be stolen from backstage, and musicians were lucky to get out of there with all their instruments.

Marv Johnson was also set to be on the Motortown Revue. The schedule had us hitting the road across the South with the Temptations, Edwin Starr, Marv, and myself on the boys’ bus—called the Funky Bus—and the Marvelettes, Martha Reeves and the Vandellas, and Mary Wells—though she had left Motown Records—on the girls’ bus. But first we heard a speech in the parking lot of Hitsville, USA, the Motown headquarters on Grand Avenue, about our code of conduct:

“We are going south, to Tennessee, Arkansas, Mississippi, Alabama and so forth. When we get to the concerts, you will see sections roped off. The white kids will be in the middle. On either side there will be the black kids. We do not want you associating with the white kids, especially the white girls. No touching, no nothing. Nothing. Because if you do, there will be trouble.”

Rightly or wrongly, “trouble” in the South sounded a whole lot more ominous for black people than “trouble” in the North did.

“When the white girls rush the stage, go to the other side of the stage. When the show is over and everyone is in the field or parking lot, there will be white girls there from the audience. You are not to speak with them. And Lord knows there will be no white girls on the bus.”

We were on the road for four or five weeks. If we didn’t stay at a boardinghouse at night, we slept on the bus. Finding food could be difficult. We would have to go to the black side of town for a restaurant or, when we pulled in too late at night, find someone willing to cook for us at home.

Traveling on the bus was crazy and it was loud. Everybody talked about music. Every guy talked about chicks. Some guys argued over sports: Who was better—Denny McLain or Satchel Paige? Singers worked on their harmonies. Musicians practiced on their instruments—Little Stevie Wonder always blowing on his harmonica. On a scale of one to ten, the noise would be at thirteen. And through all of this there would inevitably be one guy sitting up in his seat and stone-cold asleep.

There was a lot of smoking and drinking too, but there were very few problems. For the most part people were just happy to be working. If there was trouble, those at the center of it knew they would be off the tour.

That nearly happened many years later to Johnnie Taylor, who had two huge hits, “Disco Lady” and “Who’s Making Love.” Long after the Motortown Revue I emceed the Kool Jazz Festival across the country. On the bill were an all-grown-up Stevie Wonder, Aretha Franklin, Natalie Cole, Tavares, Mighty Clouds of Joy, Wild Cherry, and Taylor, who had a big alcohol problem. Sometimes he would not show up or, when he did, would go way over his time allotment on stage. A drunken Johnnie would go on and on. I would have to hustle on stage and dance him off. The promoters finally went to him and said, “Hey man, if you don’t show up or you show up and stay on stage too long, we’re going to let you go.” Johnnie was worried.

Next up was Riverfront Stadium in Cincinnati. I was in the dugout doing press for the show as the workers set up the stage at second base. Johnnie arrived, wearing a nice royal blue suit and a derby on his head, all dressed up and ready to go for his performance. “I told you guys,” he said soberly, “I’m not missing any more shows. I am here on time for today’s show.”

The stage manager looked at him and said, “That’s great, Johnnie, but the show is tomorrow.”

Back on the Motortown Revue, Edwin Starr wasn’t satisfied with simply getting on stage and singing. He had scored with the Vietnam protest song, “War,” and he was into putting on a major production. However, to cut down on expenses, he did not travel with a band; instead, he hired bands in each town to back him up. He then would go to a black church and donate money to get the choir to join him. He’d also visit local schools and donate money if twenty students would join him that night and, during “War,” run from each side of the stage to the center and pretend to attack each other, as if they were in battle.

Edwin was also a major-league conniver of women, along with Smokey Robinson and David Ruffin of the Temptations. What was surprising was that the women were not lowlifes; they were solid black citizens—schoolteachers, nurses, bank tellers. When our tour came through, these small-town girls decided they were going to grab a “star” and do something wild for once in their lives. Me? Occasionally, when there weren’t any band guys left, a young lady might settle for the emcee.

Detroit had its Motortown Revue and other cities had their hometown stars on the chitlin’ circuit too. I emceed the Philadelphia show with the Delfonics (“Didn’t I (Blow Your Mind This Time)”), Stylistics (“Betcha by Golly, Wow”), Harold Melvin and the Blue Notes (“If You Don’t Know Me by Now”), Blue Magic, and the Intruders (“Cowboys to Girls”). The Chicago package tour brought together the Dells (“Give Your Baby a Standing Ovation”), Chi-Lites (“Have You Seen Her” and “Oh Girl”), Emotions (“Best of My Love”), and Jerry “Ice Man” Butler (“Only the Strong Survive”). Many of these acts are still around today, though they have gone through large-scale personnel changes. As comic Carol Leifer has said, “I went to see the Drifters, and they had changed so much they were now white!”

The days of the police in the South setting dogs on blacks were gone, but they were not forgotten. We would overhear adult whites at the shows say, “We’re gonna hear some nigger music tonight!” or “I can’t stand that nigger music. I took my kids here because they wanted to. But I told them don’t touch any of them and don’t let them sweat on you.” Their best compliment was “These are white niggers, the ones you hear on the radio. They’re alright.” But the kids, both black and white, loved the music, and to some extent that music helped change the attitudes of whites for the better—eventually.

But after a tour in the South with any of those shows, just like after a summer with Aunt Inez in Birmingham, I was always glad to get back to New York City.

There, again at the Apollo, I opened for Marvin Gaye and Tammi Terrell. That was such a strange relationship. You might think they were lovers, but they were not. They were just the most amazing best friends—unbelievably tight. They had hits together like “Ain’t No Mountain High Enough,” “Your Previous Love,” and “Ain’t Nothing Like the Real Thing.” Then in March 1970, at the age of twenty-four, she died of a brain tumor. I worked with Gaye about three weeks later, and you could see backstage that he was crushed. He was in such heavy pain. On stage he dedicated a song to her and began to cry. He completely broke down and could not continue. Two years would pass before he would perform again in public.

Many years after my first Apollo appearance I opened for Gladys Knight and the Pips at the Westbury Music Festival on Long Island. I ordered a limousine to chauffeur my mother to the concert. She came backstage afterward. The first thing she said?

“You’re still doing the algebra question!”

4

Making It in New York

FROM THE EAST WIND TO THE APOLLO, I WAS PERFORMING IN FRONT of almost wholly black crowds. I was spinning in place so fast that I hardly knew I was not moving forward. Then someone said, “You’re not bad. Maybe you could be a more commercial act. There’s this room downtown run by a guy named Frankie Darrow who puts on comedians. He’d probably love to see what you do.” Appropriately for a black comic, it was called the African Room.

Near Times Square, on 44th Street between Sixth Avenue and Broadway, the African Room was a nightclub that, despite its name, featured limbo contests and calypso music from a Caribbean steel band led by a singer named Johnny Barr

acuda. On Monday nights though, Darrow hosted a showcase, attracting upward of twenty acts—singers, comedians, jugglers, dancers, whatever.

The audiences were still basically black, but there were also whites, and many of the showcase performers were white too. Comedians David Brenner, Steve Landesberg, and Danny Aiello, and singers Bette Midler and Melissa Manchester were a few of the unknowns trying to get on stage to do their thing. One of many acts who would never be heard from again was Three Is Company, a trio of brothers from Long Beach, New York. They tried to be a new Marx Brothers, I guess. Uh, not good. But one of the brothers did go on to fame and fortune, by the name of Billy Crystal.

Usually you had to audition to get a spot, but I came in with such energy and a different flavor that Frankie put me on right away. It was either that or he was scared I was going to shoot somebody—because I came on very strong and very ghetto.

I was far more street than the other black comics at the African Room—Stu Gilliam, Scoey Mitchell, Joe Keyes and an older comedian named Jay Bernard. He had an odd opening: “My name is Jay Bernard. That’s J-a-y B-e-r-n-a-r-d. That’s Jay Bernard. Just in case you can’t remember it, it’s Jay Bernard. J-a-y B-e-r-n-a-r-d.” He went on like that for three minutes. If a comic did that today, it would be called deconstructing comedy à la Andy Kaufman. Back then it was just stupid funny, for the first minute anyway.

Next to the stage in the African Room was a giant, eight-foot mechanical gorilla that slowly rotated back and forth and would growl as its green and yellow eyes rolled around in its head. The gorilla would continue its antics even while someone was on stage. It distracted the audience and annoyed the performer. But Darrow would only turn it off during the most popular acts.

Here was a new audience for me—the somewhat racially mixed downtown crowd. But I did the same material as I did at the Apollo, the same edgy racial humor labeled Black Only. Such as a routine about pitching pennies—about how the guys in the projects talked as they gambled, flinging pennies onto the cement, trying to land them as near as possible to a wall. The end came when someone threw a “leaner,” a rare feat in which the penny stands on its edge and leans against the wall, beating everything. I had my characters arguing and cursing like cousins at a Harlem barbershop.

If a heckler kept interrupting my act, I would use an old Redd Foxx line: “If you keep on, I’m gonna have to come out there and cut somebody!” If it was a white guy, I would hit him with “Hey man, what’s wrong with y’all? This is great shit. Oh, you’re white! Now I know why you don’t get it.” If they were black: “Ever notice how in a whole crowd of black people, a nigger always stands out?”

The problem was that even the black people in this audience wore leisure suits. These blacks had stuff, and people with stuff like having stuff and don’t want to lose their stuff. This was not the militant crowd of the East Wind who didn’t have stuff to lose. And the white people in the audience were liberals not particularly wanting to be attacked as though they were notorious Alabama police commissioner Bull Connor.

The audience would turn on me. People came up afterward and said, “What’s with the anger, man?”

One of those was Brenner. He was an Army veteran, a college graduate, and a television producer in his hometown of Philadelphia. He was smart, savvy, and had substance. He was also a very funny stand-up who you knew was going to succeed in a major way. He was white and Jewish, but he had grown up in the only Caucasian family in a black neighborhood, so he knew the black experience.

After watching me, Brenner introduced himself.

“What’s your name?”

“Jimmie Walker.”

“I’m horrible at remembering names, but I’ll remember yours,” he said, “because that was the name of a famous mayor of New York.”

He sat me down. “Have you ever worked in front of a white crowd?” he asked.

“No, not really.”

“Well, you can be a star in the black community doing what you’re doing, but if you want to be a big star, you have to learn how to make white people laugh.”

James Brown had said it was “a man’s man’s man’s world,” but most of all, it was a white world—and that was a world different from the projects and pitching pennies.

“I think you have talent,” he said. “You’re young, you have the energy, the look. But none of that will get you anywhere if you can’t get on the floor in a white club.”

He said I needed to tone down the racial rhetoric. “Hey, I understand there are problems,” Brenner explained. “The Italians have had problems, the Irish have had problems, the Jews have had problems, the Puerto Ricans, the Chinese, everybody has had problems. Jews have been persecuted for thousands of years. But you don’t hear me talking about that on stage. If you’re going to do stand-up, you need to worry about being funny. Bringing up that five thousand blacks died in Biafra today isn’t funny. You’ll have a better chance of getting a following—of being heard—if you go more middle of the road. If you keep doing what you’re doing, you will never be heard by anyone except blacks because no one else will hire you.”

When Brenner spoke, you had the feeling you should listen. And if you didn’t, he told you that you should. Brenner befriended me, and he was right. This was truly a career-changing conversation, and I knew it immediately. I wasn’t that angry young man off stage even though I played one on stage. I was never nasty, but I did have a sharp edge. If I wanted to achieve universal appeal, I now realized, my material had to relate to white people as well as black people.

That did not mean I had to become Bill Cosby. I had gone by myself to see Cosby at Carnegie Hall a year or so earlier. I brought some jokes with me, naively thinking I could lay a few on him and he would take me under his wing. But then I saw his act—in front of an audience of a lot of white people, not many black people. He told stories—like his routine about Noah—not badda-bing jokes, and nothing racially charged. They gave him a standing ovation.

I recognized that Cosby was the best comic rolling and that there has never been anyone better as a stand-up—or sit-down—comic. But what he did was not me, not my style, not my thing. I knew that my jokes were not for him, so I never approached him.

I learned that blacks and whites are different audiences. White crowds give you a few minutes to win them over. Black crowds—you have to get their attention right away. For them, I would stand on the bar. I would stand on tables. I would take a drink in my hand and yell, “Don’t think I’m not going to nigger lip this!” That would turn their heads toward me.

“You’re offending people when you say that word,” Brenner said disapprovingly of “nigger.” “People can’t laugh when they’re uptight.”

“But black people say it to each other all the time.”

“You know, white people get offended hearing that word too. People have to like you.”

I continued to use “nigger” and “whitey” or “cracker” but only when I did black gigs (I was still with the Last Poets and the Panthers). At mixed shows they became “black folks” and “y’all.”

I had a mixed act and a black act, and the mixed one was starting to succeed at the African Room. After about three months they gave me a regular spot. Then, one night as I was about to go onstage, Frankie pulled the plug on the gorilla. To this day that remains one of the highlights of my career. “I’m on my way,” I said to myself.

I began to play increasingly white crowds at clubs downtown and in Greenwich Village—from Café Wha? (where I first met Richard Pryor) to the tiny Apartment, with its wall-to-wall carpeting; from hootenanny nights at the Bitter End to Gerde’s Folk City (opening for the likes of folk stars such as Eric Anderson, Dave Van Ronk, Karla Bonoff, Bonnie Raitt, and the McGarrigle Sisters); from the Gaslight to Upstairs at the Downstairs (where Joan Rivers ruled).

At the Bitter End, if you won the Tuesday hootenanny night, determined by audience applause, your prize would be the opening-act gig for the star headliner the following wee

k. The crowd was with me one of those Tuesday nights and I won, much to the chagrin of co-owner Paul Colby, who was not a Jimmie Walker fan. He couldn’t believe I had won, couldn’t believe anyone ever laughed at my jokes.

Nevertheless, I opened at the Bitter End for Labelle, which went very smoothly because I had earlier worked with them in upstate New York when they were Patti LaBelle and the Bluebelles. We did three performances a night, at seven, nine, and eleven, from Monday through Sunday, and all twenty-one shows sold out.

I must have done okay because a writer for Variety gave me a review I still have, from 1970: “Jimmy Walker, 23-year-old black comic, is drawing yocks. . . . Material is usually ghetto-based, quite pointed and always funny. . . . When response is lukewarm, he quickly shifts gears with resulting guffaws.”

After the last of the twenty-one shows I hung around to get paid. Colby paid everyone, from the wait staff to the busboys. I think he even went outside and gave a couple bucks to the homeless guy in the alley before he finally got around to me.

He was about to hand me $50 but then stopped.

“Oh, you had two chocolate shakes,” Colby said. “That’s $1.25 a piece. Here’s $47.50.” Then he tagged it. “I’ll see you on hootenanny night!”

I was happy I could put the Bitter End on my credits and happy that I had done well, but it was clear that this comic was the low man on that totem pole.

Gabe Kaplan was a comic who insisted on getting respect, even if it was in only a token way. At the Gaslight the opening act might be a magician, followed by a comic, then a poet, and finally a headliner such as singer José Feliciano. Kaplan asked the club manager how much the comic was usually paid for the three shows a day, seven days a week.

Dynomite!: Good Times, Bad Times, Our Times--A Memoir

Dynomite!: Good Times, Bad Times, Our Times--A Memoir